It’s the time of year for saving money!

I’ve seen a lot of editorials of late wondering if music recording is at the end of its run. They lament that only the likes of Taylor Swift can actually make money on music recording, and that the art form — the recording, if not the music — may die out. But the reasons why this is nonsense were confirmed in a recent release by some of my favorite musicians, and in a recording that New York avant-jazz saxophonist David Aaron recently shared with me.

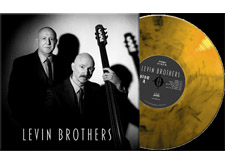

The release is Levin Brothers, a jazz album by bassist Tony Levin and keyboardist/composer Pete Levin. Tony is famous for his work with Peter Gabriel and King Crimson. Pete has worked for decades in the New York studio scene on projects ranging from the Gil Evans Orchestra to Star Trek. Although these guys are very successful musicians, they’re not swimming in money like Taylor Swift or Kanye West. Nor is Levin Brothers — which is more or less a straightahead jazz record — going to sell a zillion copies or launch them on a two-year-long worldwide tour. It’s an independent production done on a modest budget. Yet it’s an absolutely first-class recording, with great players, great tunes and great arrangements.

The release is Levin Brothers, a jazz album by bassist Tony Levin and keyboardist/composer Pete Levin. Tony is famous for his work with Peter Gabriel and King Crimson. Pete has worked for decades in the New York studio scene on projects ranging from the Gil Evans Orchestra to Star Trek. Although these guys are very successful musicians, they’re not swimming in money like Taylor Swift or Kanye West. Nor is Levin Brothers — which is more or less a straightahead jazz record — going to sell a zillion copies or launch them on a two-year-long worldwide tour. It’s an independent production done on a modest budget. Yet it’s an absolutely first-class recording, with great players, great tunes and great arrangements.

Levin Brothers also shows an entrepreneurial bent that I’m sure Taylor Swift could appreciate. They’ve maximized the profit by offering the album on CD or vinyl, not on download or streaming. The vinyl version is pricey at $29.95 — but it’s on cool gold-swirled vinyl, it includes a card that lets you download the album on MP3, and the first 1,000 are numbered and signed by Pete and Tony. I couldn’t hit the “Buy Now” button fast enough. It’s worth noting that I found out about Levin Brothers through an ad in JazzTimes magazine — an ad taken out not by the Levin Brothers, but by NS Design, which makes the electric upright bass and cello that Tony endorses and plays on the album.

You may be thinking, “Sure, those guys can put this together because they’re already successful musicians. What about the musicians who are on their way up?” But the music that saxophonist David Aaron sent me proves a great recording can be made by any musician with the drive to make one.

While Aaron does play gigs with pop and rock bands, his own music has a free-jazz, avant-garde bent that he’s never compromised for the sake of a buck. Yet for the last 15 years or so, he’s managed to make and release high-quality recordings. The one he recently sent me, recorded by engineer Hugo Dwyer in Aaron’s living room, with his jazz trio Flip City, captivated me not only with the performance (honed by playing innumerable gigs in small New York City jazz clubs), but by the recording, which has an intimacy I love and all the audiophile twists I crave, including rock-sold imaging, accurate tonality and an enveloping soundstage. You can check it out in the link below. Be forewarned: This ain’t Kind of Blue. But the fact that such challenging, non-commercial music can be recorded and distributed just helps prove my point.

Aaron accomplishes this by cultivating and maintaining relationships with talented musicians and engineers in the New York City area. He’s never waited around for some record company to do something for him; he decides he wants to make a recording, then he finds a way to make it happen.

Thanks to the dramatic reduction in cost of high-quality audio recording gear, any musician with the will to learn the recording craft (or build relationships with people who’ve already learned it) can make and release recordings. And if they have some of the Levin Brothers’ entrepreneurial drive, they stand a good chance of getting them heard.

It’s likely that musicians will from this point forward only rarely make much money from their recordings. But the idea of musicians making much of their living from recordings has really only been around since the 1970s. Music, as an art form and career, has been around for at least 1,000 years — and as a hobby, for something like 50,000 years.

It’s likely that musicians will from this point forward only rarely make much money from their recordings. But the idea of musicians making much of their living from recordings has really only been around since the 1970s. Music, as an art form and career, has been around for at least 1,000 years — and as a hobby, for something like 50,000 years.

Sure, the practice of musicians going into expensive studios for weeks or months, fueled by bacchanalian budgets, is mostly over. We may never get another Rumours. But in the bargain, we will get many, many more recordings by artists whom the record companies might have overlooked 30 years ago, and who back then could never have afforded to make a good recording on their own.

Music recording isn’t dead. It’s better than ever.