It’s the time of year for saving money!

Super Audio CD (SACD) was introduced in 1999 by Philips and Sony, its co-inventors, as the next generation of consumer audio, featuring six channels of Direct Stream Digital (DSD), the highest resolution then available to home listeners, and backward compatibility to existing CD players through its hybrid CD layer.

My Sony and Philips colleagues and I demonstrated DSD surround recordings of classical, jazz, and rock music to several hundred leading recording engineers, musicians, and reviewers, using top-quality playback equipment in acoustically treated environments. We received almost unanimous praise for their transparency. Reviewers exulted over its lack of digital harshness, and one well-known engineer told me that while 96/24 PCM sounded good, with DSD he heard the output of his console, not the output of the recorder.

My Sony and Philips colleagues and I demonstrated DSD surround recordings of classical, jazz, and rock music to several hundred leading recording engineers, musicians, and reviewers, using top-quality playback equipment in acoustically treated environments. We received almost unanimous praise for their transparency. Reviewers exulted over its lack of digital harshness, and one well-known engineer told me that while 96/24 PCM sounded good, with DSD he heard the output of his console, not the output of the recorder.

Interestingly, one major artist A/B compared this engineer’s simultaneous 96/24 PCM and DSD recordings of her music in his control room and told him, “We can’t go back.”

Consumers could buy SACDs before they bought surround systems and their purchases wouldn’t be obsolete when they upgraded. The same discs would play in their cars, their portable players, their children’s boom boxes, and the surround systems in their listening rooms.

Further, DVD-Video was making significant progress in homes, helped by low-cost but low-quality “home theater in a box” surround systems. One might assume that surround audio on a CD-sized disk would be an easy sell.

Further, DVD-Video was making significant progress in homes, helped by low-cost but low-quality “home theater in a box” surround systems. One might assume that surround audio on a CD-sized disk would be an easy sell.

So why was SACD not a commercial success?

First, there was a format war. The DVD Forum, headed by Toshiba, refused to pay patent royalties to Sony and Philips, and they launched a competing format: DVD-Audio, which couldn’t be played in a CD player. Ironically, the royalty for an SACD was the same as for a CD: $.10 per disc, while the royalty on a DVD-Audio disc was around four times higher.

Record labels chose sides. The Warner group, part of the DVD Forum, went with DVD-Audio, and Universal and Sony chose SACD. Consumers are understandably reluctant to choose one new format over another — they remembered the Beta vs. VHS format war — so neither SACD nor DVD-Audio gained significant traction.

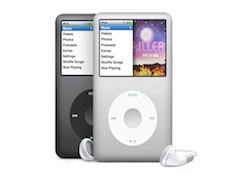

Then came the bombshell. Like Monty Python’s Spanish Inquisition, nobody expected the iPod. While there were MP3 players that preceded the iPod, they were clunky, difficult to use, and thus had limited success. Steve Jobs and his crew put a simple, straightforward user interface in an elegant package that was a huge hit. Never mind that it used MP3 files (although it could also play PCM files).

Then came the bombshell. Like Monty Python’s Spanish Inquisition, nobody expected the iPod. While there were MP3 players that preceded the iPod, they were clunky, difficult to use, and thus had limited success. Steve Jobs and his crew put a simple, straightforward user interface in an elegant package that was a huge hit. Never mind that it used MP3 files (although it could also play PCM files).

The mass market fell in love with the iPod. Consumers didn’t care that its supplied earbuds were poor quality and that its MP3 files didn’t sound as good as CDs, let alone high-resolution. Then Apple released its iTunes software, first for the Mac and then for Windows, and they started selling music at $.99/track through the iTunes Music Store. Apple made it easy for the average consumer to buy music and carry it in a convenient package.

The money that consumers would have spent by on high-resolution surround sound instead went to portable music, and the demand needed to establish a viable high-resolution format never materialized.

When we look back, we see that acoustical recordings, which started around the turn of the century, were replaced by electrical recordings in the mid-1920s. The LP and the 45 replaced those in the late 1940s and evolved into stereo records in the late ’50s. The CD took hold in the early 1980s. SACD and DVD-Audio may have been too early, as they were introduced in 1999 and 2000, respectively, but the iPod’s introduction in 2001 sealed their fate.

When we look back, we see that acoustical recordings, which started around the turn of the century, were replaced by electrical recordings in the mid-1920s. The LP and the 45 replaced those in the late 1940s and evolved into stereo records in the late ’50s. The CD took hold in the early 1980s. SACD and DVD-Audio may have been too early, as they were introduced in 1999 and 2000, respectively, but the iPod’s introduction in 2001 sealed their fate.

By about 2007, DVD-Audio was a dead format. Some audiophile labels continued to release SACDs. 2L and a few other labels are releasing high resolution recordings on Blu-ray discs, but with the wide availability of high-speed internet connections and relatively low-cost, high-capacity digital storage, the market for music on disc is vanishing.

Garry Margolis is an independent consultant based in Los Angeles. He produced and engineered analog recordings and supervised their mastering and pressing, then joined JBL Professional and UREI, where he was involved in the specification and voicing of studio monitors and high-end consumer systems.

He was Philips’ North American liaison to the motion picture and recording industries for technologies including MPEG Multichannel audio, Super Audio CD, and Blu-ray.

He is a Past President of the Audio Engineering Society and currently serves as its Treasurer.