It’s the time of year for saving money!

In Part I of this new series, I wrote about the very first electrical phono cartridges; those that used the wiggling of a “needle” as it tracked the record groove to bend either Rochelle salts crystals or a piezo-electric ceramic material and produce voltage that would drive an amplifier and make music.

Before those, the very earliest record playback devices hadn’t even been electrical, but had relied on the needle’s movement to directly drive a diaphragm to produce the sound, which then usually came out through an “amplifying” horn. (Remember Nipper the RCA dog? Sitting by the horn and listening and listening to “his master’s voice”?) Even though their sound wasn’t even close to the best of modern standards, those early crystal and ceramic cartridges were a vast improvement over their acoustic predecessors and, even as late as 1957, when Electro-Voice produced the very first commercially available stereo phono cartridge, it was ceramic and – even as compared with the then-new “magnetic” cartridges like the GE “variable reluctance”-type that was the absolute game-changer for phono reproduction – they didn’t sound bad at all.

Before those, the very earliest record playback devices hadn’t even been electrical, but had relied on the needle’s movement to directly drive a diaphragm to produce the sound, which then usually came out through an “amplifying” horn. (Remember Nipper the RCA dog? Sitting by the horn and listening and listening to “his master’s voice”?) Even though their sound wasn’t even close to the best of modern standards, those early crystal and ceramic cartridges were a vast improvement over their acoustic predecessors and, even as late as 1957, when Electro-Voice produced the very first commercially available stereo phono cartridge, it was ceramic and – even as compared with the then-new “magnetic” cartridges like the GE “variable reluctance”-type that was the absolute game-changer for phono reproduction – they didn’t sound bad at all.

The two great advantages of crystal and ceramic cartridges were 1) their comparatively huge output, [as much as two full Volts – hundreds or even thousands of times the output of some magnetic cartridges] and 2) the fact that they, just by their natural frequency response characteristics (boosted bass; rolled-of treble), naturally compensated for most recording equalization standards to at least a major degree and, accordingly, made phono playback equalization largely unnecessary. (I commented on these two characteristics last time, saying that, with ceramic cartridges still being available and cheap, they might be a great low-cost- little-concern choice for people who wanted a record player but were afraid of kids or cats breaking something better [read “more expensive”], or didn’t have an amplifier, preamp, or receiver with a “phono” section.)

Sonically, though, the “magnetic” phono cartridge was, from its first introduction, the clear winner – the sine qua non of audiophile phono reproduction for those who insisted on the best they could buy. So naturally, I, at all of thirteen or fourteen years old, had to have one. That meant, back then, in the mid-1950s, that I had to buy a phono preamp (PRE-amplifier) to perform the twin functions of boosting my GE cartridge’s very low output (only 5 or 10 millivolts, as I recall, instead of the Volt or even two of the cartridge I was replacing) and providing the necessary playback equalization (which the GE, with its “flat” frequency response, couldn’t do).

Sonically, though, the “magnetic” phono cartridge was, from its first introduction, the clear winner – the sine qua non of audiophile phono reproduction for those who insisted on the best they could buy. So naturally, I, at all of thirteen or fourteen years old, had to have one. That meant, back then, in the mid-1950s, that I had to buy a phono preamp (PRE-amplifier) to perform the twin functions of boosting my GE cartridge’s very low output (only 5 or 10 millivolts, as I recall, instead of the Volt or even two of the cartridge I was replacing) and providing the necessary playback equalization (which the GE, with its “flat” frequency response, couldn’t do).

That first preamp that I bought to amplify the signal from the cartridge enough that the amplifier could use it (hence the term “pre” amplification) was a one-tube unit (one 12AX7, as I recall) from Fisher Electronics (the firm started by audio pioneer, Avery Fisher). It cost me the (for a kid) princely sum of $13 and had built-in “fixed” equalization to (probably) the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) standard. I say “probably” because there were, at the time, any number of recording “standards” – very often one per major record company – and, before the industry finally settled on the RIAA standard, I remember amplifiers (we would call them “integrated” amplifiers today) that had on their selector switches as many as nine separate choices of phono equalization.

It may very well have been this profusion of recording standards and the need for audiophiles with the latest phono cartridges to have the right playback EQ available to play the right record that resulted in the modern “control preamp” and separate power amplifier. Although, the trend toward separate components instead of “hi-fi consoles” (one-cabinet floor-standing systems including record player, radio, amplifier, and speaker (remember stereo records didn’t come along until 1957) or “receivers” (amplifiers, available even today, with a built in radio tuners — AM, FM or both) was well under way by the mid ’50s, (and probably found its culmination in the 1980s, when the CD player was separated into transport and DAC) it may very well have been the advent of the magnetic phono cartridge and its need (at least until RIAA finally became ubiquitous) for specific record label-by-record label playback equalization that speeded it along.

It may very well have been this profusion of recording standards and the need for audiophiles with the latest phono cartridges to have the right playback EQ available to play the right record that resulted in the modern “control preamp” and separate power amplifier. Although, the trend toward separate components instead of “hi-fi consoles” (one-cabinet floor-standing systems including record player, radio, amplifier, and speaker (remember stereo records didn’t come along until 1957) or “receivers” (amplifiers, available even today, with a built in radio tuners — AM, FM or both) was well under way by the mid ’50s, (and probably found its culmination in the 1980s, when the CD player was separated into transport and DAC) it may very well have been the advent of the magnetic phono cartridge and its need (at least until RIAA finally became ubiquitous) for specific record label-by-record label playback equalization that speeded it along.

Thus far, I’ve just been referring to “magnetic” cartridges in the generic sense, meaning anything that has low output; that needs playback equalization – not because of any flaw in performance, but because its “flat” frequency response can’t compensate for equalization added during the recording process the way crystal or ceramic cartridges (largely) can; and that produces its output by magnetic, rather than piezoelectric or other means.

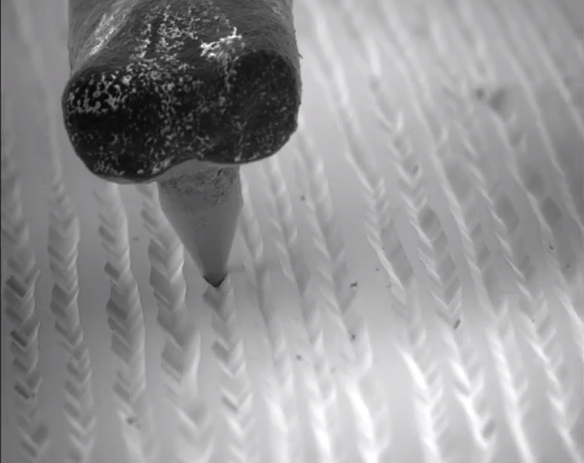

Just as all “piezo” cartridges (the crystal and ceramic ones) work by using the groove-induced motion of the stylus (the “needle”) to bend or stress a crystalline or equivalent structure, all magnetic cartridges produce their output by using the motion of the stylus to cause something to interrupt magnetic lines of force and induce a voltage in at least one (for mono) or more (for stereo) included coils.. The thing that changes from one kind of magnetic cartridge to the next is which part of the cartridge is doing the moving.

Just as all “piezo” cartridges (the crystal and ceramic ones) work by using the groove-induced motion of the stylus (the “needle”) to bend or stress a crystalline or equivalent structure, all magnetic cartridges produce their output by using the motion of the stylus to cause something to interrupt magnetic lines of force and induce a voltage in at least one (for mono) or more (for stereo) included coils.. The thing that changes from one kind of magnetic cartridge to the next is which part of the cartridge is doing the moving.

The basic parts complement of most magnetic cartridges consists of a stylus, which is the actual “needle” that rides in the groove to pick up the sound; sometimes, but not always, a cantilever, which, if present, is the moving “platform” to which the stylus and other parts may be mounted; a magnet, which must always be present and may or may not be one of the things mounted to the cantilever; a bit of iron, which, if the magnet is not mounted on the cantilever, might be mounted there, instead, or left off entirely; the pivot, which allows the cantilever to move to allow the stylus to follow the groove; and the coil(s), which may or may not move, but if they do, will likely be mounted somewhere on the cantilever.

All of these elements (or at least all of those present) will be brought together to form a magnetic cartridge of one of three basic kinds, identified by which part or assembly does the actual moving to produce its output: The first is the “moving magnet”; the second is the “moving coil” and the third (which some regard as just a variant on the first) is the “moving iron”. Of these, one which became hugely popular in the audiophile community, was rejected by its inventor as “never likely to amount to much” and, though patented, was never used in any of his production designs.

I’ll tell you more about all of them next time.

I hope to see you then.