It’s the time of year for saving money!

Audiophiles are dedicated to the improvement and refinement

in the quality of the sound they hear from their sound systems. They change

interconnects and listen for improvements. They change components and listen

for improvements. They usually use familiar recordings as a reference to help

them determine if there are improvements.

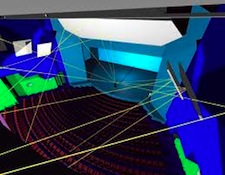

A good part of how a system sounds depends on its setup and

speaker position. An equally important aspect of the set-up is how close the

speakers are to the front and side walls of the room, as well as how close the primary

listening position is to the back wall. Eventually most people discover there

is more to how the system sounds than merely its geometry of the listening

room.

When an upgrade is made in a system a perceptible improvement

in sound quality is usually delivered to the listening position, which

justifies the investment. As the upgrade process progresses, eventually a

better piece of electronics that “should” have made a noticeable improvement,

doesn’t. Here’s where the evolution of the audio system often grinds to a halt.

Product reviewers may have given a new piece of gear raves, but

what happens if it doesn’t make any difference at home? Is there a problem with the equipment,

manufacturer, dealer or reviewers? Probably not, but the audiophile may have

reached a performance plateau. From this point on any further electronic

attempts to improve a system will remain inaudible.

Lacking the ability to detect any further improvements in their

system, audiophiles frequently resort to entertaining upgrades that may not

necessarily “improve” the system’s performance, but do create detectable

changes in the performance. However these artifact styled “improvements” become

boring after a while, because they add the same accent to all music, making it

sonically one-dimensional.

For most audiophiles hitting the upgrade wall is a big

disappointment. They hear better performing systems in other rooms, but since

they can’t seem to get their system to perform better. Faced with this dilemma

some audiophiles resign themselves to their lackluster systems as defining the

end of the road. They give up on the idea of trying to get better sound.

Let’s take a look at

what is really going on.

If program material is buried too deep in the noise floor, no

one can hear it, even though it is there. The noise of an LP record creates a

noise floor that is about 40 dB below the main signal level. Tape machines are

better, with a tape hiss noise floor that was about 60 dB below the main signal

level. And with digital, the signal to noise ratio can be 100 dB or more.

The problem is never about hearing or not hearing the main

signal. The problem is hearing the subtle detail within the signal. The main

signal will always have a strong tonal presence that combines with dozens of

lower level partials or overtones. Some overtones are very low in level. When audiophiles

listen over quality headphones even these quiet musical details are readily

apparent. But when the same selection is played back through a room-based sound

system, these quieter musical details disappear, rendering the playback less

involving.

Through reading, web forums and discussions with friends some

audiophiles begin to imagine that the problem might not be with the electronics

of the system, but with the acoustics of their room. The room acoustic is

creating a higher noise floor that is masking the fine, low level musical

detail.

A sound meter shows that music is typically played at a level

of about 75 dB, A-weighted, It also shows that the background noise floor in

the room, with all the music off, is about 25 dB A-weighted. That means there

is a 50 dB signal to noise ratio in the room acoustics. This is the steady

state signal to noise ratio.

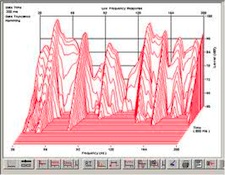

The problem with listening to sound in a room is that once we

hear the sound, it continues to be reflected around the room until the sound

dies. And music isn’t merely one sonic event followed by a reverberant decay. There

are, on average, about eight separate dynamic sonic events per second, each of

which is followed by their own reverberant decay.

In small room it takes, on average, at least one second for a

particular sound to die down enough so it becomes inaudible. Playing music in

small rooms increases the self-noise floor, which is made up of the various

reverb levels from the music that’s been played during the previous second. The

strength of this self-induced noise floor can equal or exceed the strength of

the direct signal.

When audiophiles listen to a recording over good headphones

they experience a signal that has a very quiet background noise floor. But the

same program material played in a listening room produces a 0 dB to -5 dB

signal to self-noise ratio. Low-level musical detail typically exists in the

range of -20 dB. Over headphones, low-level details remain audible, but in a

room these details are buried in the room’s acoustic self-noise floor.

Audiophiles work on room acoustics because beyond a certain

point in the evolution in the performance of their audio system reducing the

room acoustic self-noise floor in the room becomes the only possible

improvement they can make.

But the ironic thing is that it’s not until after room acoustic

upgrades are finished, that further improvements in the electronics become

audible. But audible progress occurs only to that point where the room’s self-noise

floor again has to be addressed. And back and forth it goes, alternating

between electronic upgrades and room acoustic upgrades, continually stepping

forwards towards perfection in high-end audio

Art Noxon is a fully accredited Acoustical Engineer with

Master of Science degrees in Mechanical Engineering/Acoustics and Physics. A

professional engineer since 1982, Mr. Noxon is licensed to practice engineering

in the public domain with a specialty area of acoustics. He is the inventor of

the TubeTrap, the original corner-loaded bass trap with built-in treble

diffusion. He is the president of Acoustic Sciences Corporation.

I’ve been saying for years this is the main reason I don’t make blanket statements in my audio reviews, like “this is the best amplifier” – because the room contributes to everything, and all our rooms are different!

GREAT read as always Steven!

Many years ago as a broadcast engineer I launched a project to survey average listening environments for my station’s target audience. I was so dismayed by the functional signal to noise ratios encountered I abandoned the survey, went back to the station and squashed the heck out of the dynamic range just like the PD wanted.

As a neophyte audiophile, I have read hundreds of articles on the internet and magazines about the importance of listening rooms. Long ago I could build me a room for stereo audio and home theater, which knowing the importance of room acoustics, the design proportions obtained approximately the fibonacci sequence (the golden ratio), but the builder did not run correctly (3 x 5.2 x 8.15 meters). I have also hand made a sound absorbers and tubetraps with Owens Corning fiberglass used for air conditioning ducts. All that explains the sr. Noxon is correct, I could verify this to make changes to both cables and equipment, locations of speakers, listening position and acoustic treatments themselves. For example, the most dramatic improvement personally went with the tubetraps, I made only three tubetraps 2 meters high by 0.5 wide, placing them in the corners of the front wall behind the speakers and one in the middle. More dramatic was moving them to the back wall behind the listening position, so it seemed logical, since the sound of the speakers and subwoofer travel from one end where they are located ahacia the back wall, reducing the increase in qe serious is done corners. Another conclusion I have drawn is that the tubetraps installed, the position of the subwoofer is not so important that without tubetraps. Finally, the only disadvantage of placing many sound absorbers is that the apparent volume of the music is greatly diminished, so I’m considering installing six curved diffusers (1/4 circumference) of aluminum and 2 meters high by 0.8 wide.

Hopefully this experience will help someone improve their living. I have Bryston electronics, Denon DVD, Advent Heritage speakers with internal cables AudioQuest Tipe 4 plus, Velodyne sub, cables of various brands (PS Audio, Xindak, Audioquest, Monster and Madrigal).

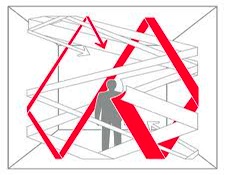

There are two basic acoustic conditions of the listening room which precede the reverberant buildup. The first one is what I call “head end ringing”. It is the violent quivering of the air in the front 1/3rd of the room as the bass from the speakers expands sideways and vertically. This 2/3rds of the sonic energy being dumped into the room is trapped momentarily in the front 1/3rd of the room and becomes very loud. This trapped energy quickly turns into the sound of chaos being created in the front of the room. Although it is traveling perpendicular to the listening axis of the room it slowly expands and within 1/10th of a second it engulfs the listener, obscuring the details of literally the onset in the in the next musical event. After this vertical/lateral energy fills the room, only then does it become reverberation….

From the very beginning in the life of TubeTraps they were always placed in the front two corners of the room. These days we even add more to the side walls in the front of the room, to help quiet down front end ringing which brings great clarity to the music, sound stage and image detail.

An aside: Yes, early side wall reflections are important to control.

There are two of them. When the left speaker bounces off the left wall, it widens the sound stage. When the left speaker bounces off the right wall, left sound enters the right ear, which totally confuses the left-right stereo image effect. But this is all in the treble range. The problem with sound panels is that it leaves a sonic black hole on either side of the listener, which is audible and instinctively alarming. When we do rooms, we use small 9” or 11” TubeTraps along the side walls and we rotate the diffusing side towards

the back of the room. The dead side of the traps faces the speakers and absorbs the early reflections but the live side of the traps scatter the late, low level reflections off the back wall towards the listener which creates the acoustic condition of spaciousness, where there would have otherwise been a zone of nothingness.

The second condition is in the long dimension, and focuses

on the rear wall. We need lots of huge bass traps to punch a hole in the reflection of the deep bass waves off the rear wall. All diffusing surfaces here are oriented into the room to keep the ambiance up.

An excellent upgrade to room acoustics is to remodel the walls and ceiling of the listening room so they are no longer thunder plates and a source of nagging shuddering sonic afterglow. This is done by adding constrained layer damping to the construction of your room. We supply WallDamp for that purpose. This not only calms down the surface of the room but it also turns the entire room into a deep bass membrane bass trap, perfect for subwoofer energy conditioning and at a cost of about $1.50/sqft of wall and ceiling surface, it is such a bargain you cannot even begin to imagine.

I’d like to see an article about computer room treatment, and would be interested in Mr. Noxon’s view of the necessity of treatment when such other treatment is used.

Putting a computer in a room does not change the decay rate of sound in the room and so I’d say the computer does not “treat” the room. What it does is to treat the signal being delivered to the room.

See http://www.asc-hifi.com/articles/tas-roundtable.htm for a transcription of an interview by TAS between me, representing acoustics, a computer room treatment manufacturer and a product reviewer. The computer acoustic people said they always trap the room acoustically first and then add computer controls to help manage the remaining irregularities in sound level. It wasn’t about either/or but about one helping another.

I’m always surprised when audiophiles consider introducing trick electronics into their audio chain. “Back when” the idea was linear electronics, to get the electronics to deliver a perfect reproduction of the source material to the convergent point of the speakers. And then address room acoustic induced distortion by using room acoustics.

An interesting product needs to be mentioned here, the eTrap by Bag End. It can absorb energy out of a single frequency standing wave. It senses and pushes air similar to how we sense and push a child on a swing when we want to reduce the height of the swing, We apply pressure out of phase with the swing.

I’ve said repeatedly that a good listening room and good speakers are the two most important components in any audio system, and should be the first two things to be dealt with! If you don’t have those two things, you can’t make valid judgments on any other components in the system!

I had to combine my 2 channel listening with home theater because of space constraints. I used the basic acoustic treatment…first reflection, bass traps in corners, etc. But I also built a baffle wall and used an acoustically transparent screen. I found the baffle wall to be the single most important thing I did (for my room). So much so that I could not tell the difference between good quality speakers and the high quality ones I replaced them with (based on price).

I ended up selling the high enders and building my own active speakers with medium quality components, and to my ear they sound just as good in my room (at about 1/8 the price). I am sure there is some placebo effect here as I built them myself, but it just wasn’t worth the price of keeping the expensive speakers if I coudn’t here the difference…placebo or not.

IMO the room treatment should be the first thing on the list, or at least combined with the original purchase.

With the general high quality of sound reproduction from most of every-day HT systems, room acoustics is the most important factor influencing how well the system sounds. I use a combination of electronic and physical compensation to a very noticeable positive effect.