It’s the time of year for saving money!

Many years ago I acquired a tee-shirt from Mapleshade Records. On the back it read in big bold letters, “No Compression, No Limiting, No EQ!” Obviously in Mapleshade’s world these are all very bad things that should not be used on a recording. But is this a universal truth? I would say, no, it is not. A limiter, compressor, or equalization device is really no different from a Sawzall or nail-gun. In the right hands they make for a better final result, but in the wrong hands can completely mess things up.

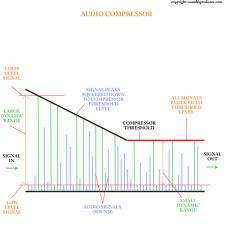

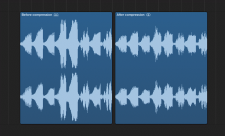

Time for some theory. What and how does a compressor and a limiter work? A compressor is a device that restricts the dynamic range of a mic feed somehow. It can do this by raising the level of the quietest sounds or lowering the peaks of the loudest ones. The result is a dynamic range, from loud to soft, that fits onto a recording. And why would you need to adjust the naturally occurring dynamic range? The primary reason is that you have instruments whose range from loud to soft is greater than the dynamic range of your recording medium. A second and equally important reason is when the instruments playing together that have differing dynamic ranges. Adding a drum kit to an acoustic group is one situation where the drums have the potential to be much louder than any of the other instruments in the group. A good percussionist can adjust his range to match other players, but even a great drummer will occasionally play one hit that is a bit too loud and would otherwise spoil a recording by exceeding the dynamic peaks that a recording medium can capture without distortion. The solution is to limit the drum’s loudest levels by using a limiter.

Time for some theory. What and how does a compressor and a limiter work? A compressor is a device that restricts the dynamic range of a mic feed somehow. It can do this by raising the level of the quietest sounds or lowering the peaks of the loudest ones. The result is a dynamic range, from loud to soft, that fits onto a recording. And why would you need to adjust the naturally occurring dynamic range? The primary reason is that you have instruments whose range from loud to soft is greater than the dynamic range of your recording medium. A second and equally important reason is when the instruments playing together that have differing dynamic ranges. Adding a drum kit to an acoustic group is one situation where the drums have the potential to be much louder than any of the other instruments in the group. A good percussionist can adjust his range to match other players, but even a great drummer will occasionally play one hit that is a bit too loud and would otherwise spoil a recording by exceeding the dynamic peaks that a recording medium can capture without distortion. The solution is to limit the drum’s loudest levels by using a limiter.

Another example of a situation where limiting is absolutely necessary is that old audiophile chestnut, Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture.” The problem is that the “cannons” (or squibs or cherry bombs) used for the finale are substantially louder than any orchestral instrument (and the entire orchestra put together). During live performances the cannons are limited by moving them far enough away from the stage so they are in balance with the orchestra. That is a form of limiting using distance instead of a device. On the famous Mercury Living Presence recording the liner notes detail how the cannons were recorded separately, outdoors, from some distance away, to get the right balance in the final mix.

The other problem that compression can solve is when a particular sound, player, or instrument is too quiet and can’t be heard in the mix. Here a compressor can raise the level of the quietest sounds on one track of a multi-track recording while not affecting the louder ones. An example would be a song that has finger snaps. These snaps could need some boosting to fit into the mix correctly and some limiting to keep the loudest snaps from being too present. Both aims can be accomplished through limiting and compression.

The other problem that compression can solve is when a particular sound, player, or instrument is too quiet and can’t be heard in the mix. Here a compressor can raise the level of the quietest sounds on one track of a multi-track recording while not affecting the louder ones. An example would be a song that has finger snaps. These snaps could need some boosting to fit into the mix correctly and some limiting to keep the loudest snaps from being too present. Both aims can be accomplished through limiting and compression.

And what is the basic difference between a compressor and a limiter? The difference is only in the compression ratio used. A limiter is intended to limit the maximum level, normally to provide overload protection. For this the unit is set so the threshold is close to the maximum desired audio level, using a very steep ratio (anything above 10:1). This means is that the input signal needs to go 10dB above the threshold before the output will rise 1dB above it.

A compressor is used for less drastic dynamic control with lower ratios; typically 5:1 or less. A ratio of 2:1 means that for every 2dB of input level above the threshold, the output level only rises by 1dB.

The other significant difference between a compressor and limiter is that a limiter usually has faster attack and release times, so that it can respond to brief transient peaks with optimum efficiently. Compressors are usually set with a slower attack specifically so that they don’t squash the attack transient on percussive sounds. They also usually have a slower release so that their gain changes are gentler; more like pushing a fader up and down.

The other significant difference between a compressor and limiter is that a limiter usually has faster attack and release times, so that it can respond to brief transient peaks with optimum efficiently. Compressors are usually set with a slower attack specifically so that they don’t squash the attack transient on percussive sounds. They also usually have a slower release so that their gain changes are gentler; more like pushing a fader up and down.

So, there you have a brief treatise on why you shouldn’t be badmouthing limiting and compression any more than you badmouth a ball-peen hammer. Blame the folks who use the tool wrong, not the tool itself…