It’s the time of year for saving money!

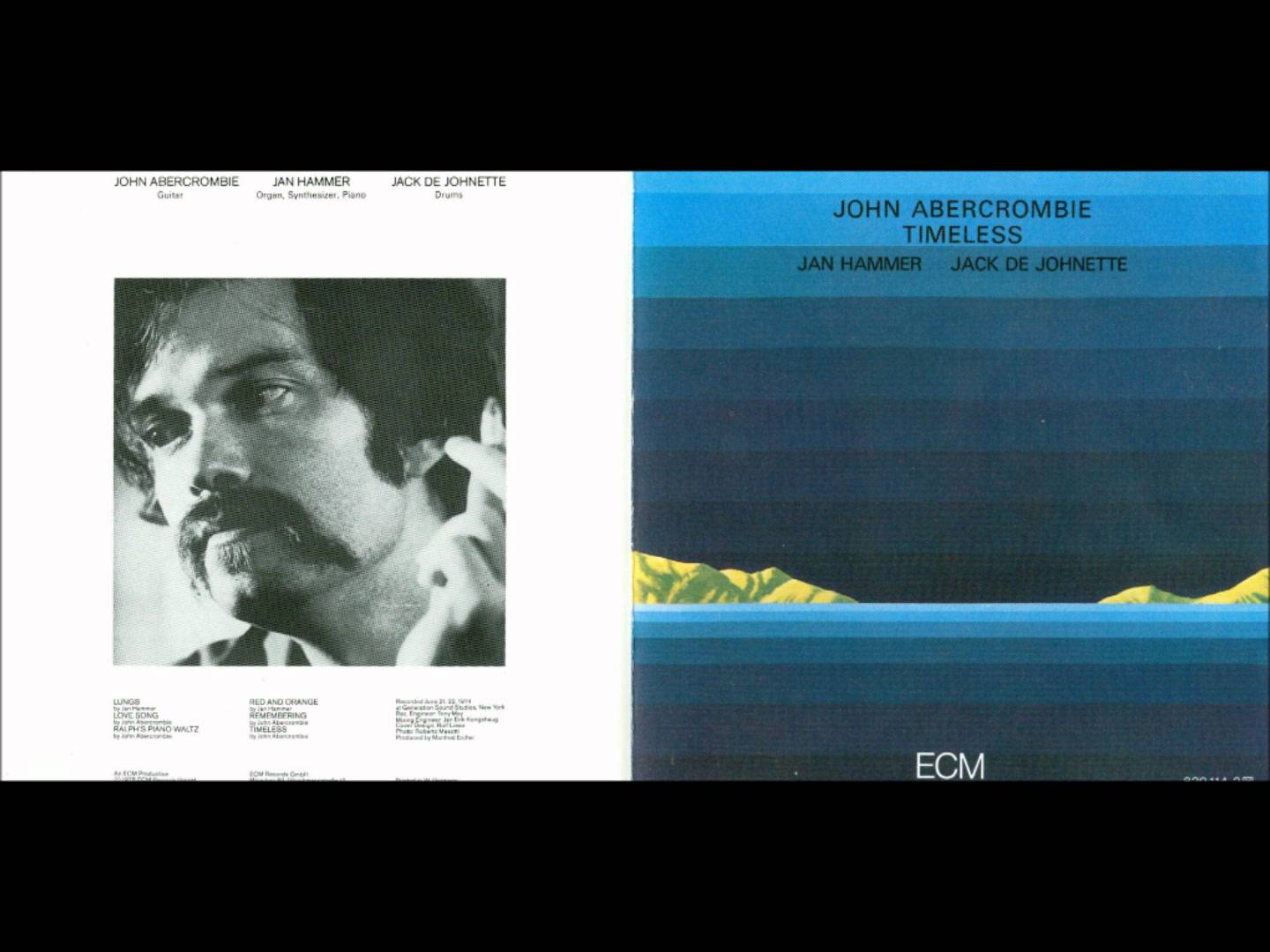

I dropped by Joe’s place recently. I fired up his home system and played an old favorite that he had on CD, Timeless by John Abercrombie. It sounded great, a fusion jazz classic from 1975 with Abercrombie on guitar, Jan Hammer of keyboards, and Jack DeJohnette on drums. The long title track sounded transcendent in a bluesy, mystical, fusion kind of way with the opening synthesizer rifts by Hammer followed by Abercrombie improvising melodious free jazz. Joe and I lamented Abercrombie’s recent passing, and Joe asked where he collect more of his albums without just browsing TIDAL or buying more CD’s and, ideally, with even better sound quality. “Can I do that, Andy?” “Sure,” I replied. “You can find most of Abercrombie’s work, at least on the ECM label, at a website specializing in high-quality, high-resolution downloads called HDTracks.com.” “Really? Tell me more!” Joe seemed excited.

We powered up his 15″ MacBook Pro, a nice space gray one, launched Chrome, and entered the URL http://www.hdtracks.com. Without even creating an account, Joe searched for “John Abercrombie”. Timeless came up as second album in the search results list, with label, “192/24” beneath the thumbnail image of the album cover. Joe appeared puzzled. I explained that when you purchase high-quality or high-resolution downloads, the files often contain a lot more musical information than you’ll get on CD or find on TIDAL Hi-Fi. The 192 refers to the sample rate, the higher the number directly proportional to the overall range of frequencies in the download going from very low to very high. The 24 referred to the number of bits holding each “sample”, a measure of amplitude at any given moment in the recording. Again, the higher the number, the more potential dynamic range. CD’s and TIDAL HI-Fi would have the numbers “44.1/16” associated with them. That’s not bad, but “192/24” should result in greater fidelity because, put simply, the container holding the music has a larger envelope of reproducible lows and highs and greater overall dynamic range, or difference between the softest and loudest passage, so the music has a little more room to breath, speaking metaphorically.

We powered up his 15″ MacBook Pro, a nice space gray one, launched Chrome, and entered the URL http://www.hdtracks.com. Without even creating an account, Joe searched for “John Abercrombie”. Timeless came up as second album in the search results list, with label, “192/24” beneath the thumbnail image of the album cover. Joe appeared puzzled. I explained that when you purchase high-quality or high-resolution downloads, the files often contain a lot more musical information than you’ll get on CD or find on TIDAL Hi-Fi. The 192 refers to the sample rate, the higher the number directly proportional to the overall range of frequencies in the download going from very low to very high. The 24 referred to the number of bits holding each “sample”, a measure of amplitude at any given moment in the recording. Again, the higher the number, the more potential dynamic range. CD’s and TIDAL HI-Fi would have the numbers “44.1/16” associated with them. That’s not bad, but “192/24” should result in greater fidelity because, put simply, the container holding the music has a larger envelope of reproducible lows and highs and greater overall dynamic range, or difference between the softest and loudest passage, so the music has a little more room to breath, speaking metaphorically.

Of course, the price is higher. The 192/24 version of Timeless cost $17.98. Joe created an account with his email address, a password, and his credit card information. He added Timeless to his shopping basket and checked out. HDTracks gave him the choice of several file formats, and I suggested FLAC, which uses lossless compression to minimize download time and save storage space but not actually lose any musical information. Joe had to install the download manager, which quickly organized all six tracks of Timeless into a single folder on his MacBook Pro’s internal drive. Then he followed some simple instructions in the Aurender N100H manual so that his MacBook Pro could see the N100H’s fixed drives on Joe’s home network. Then he just copied and pasted the whole album from his MacBook Pro to the N100H and told the N100H to scan for new files via the Aurender Conductor App on his iPad. Simple? Kind of. He found the 192/24 version of Timeless via the Conductor App and touched the play icon.

Of course, the price is higher. The 192/24 version of Timeless cost $17.98. Joe created an account with his email address, a password, and his credit card information. He added Timeless to his shopping basket and checked out. HDTracks gave him the choice of several file formats, and I suggested FLAC, which uses lossless compression to minimize download time and save storage space but not actually lose any musical information. Joe had to install the download manager, which quickly organized all six tracks of Timeless into a single folder on his MacBook Pro’s internal drive. Then he followed some simple instructions in the Aurender N100H manual so that his MacBook Pro could see the N100H’s fixed drives on Joe’s home network. Then he just copied and pasted the whole album from his MacBook Pro to the N100H and told the N100H to scan for new files via the Aurender Conductor App on his iPad. Simple? Kind of. He found the 192/24 version of Timeless via the Conductor App and touched the play icon.

We heard the same album, but it sounded different. The listening experience seemed effortless, like listening to reel-to-reel tape. Neither louder nor softer, not warmer or brighter, we just heard more “there” there and felt more drawn into the music. “Why does this sound so much better, Andy?” “It begins with DSP, or Digital Signal Processing.” “You mean things like Auto-Tune that correct people singing off key?” “That’s one application, but a kind of extreme one. Even the simplest devices that record and play sound digital digitally use DSP.” I showed Joe a short list of DSP definitions relating to the everyday audiophile and music enthusiast.

We heard the same album, but it sounded different. The listening experience seemed effortless, like listening to reel-to-reel tape. Neither louder nor softer, not warmer or brighter, we just heard more “there” there and felt more drawn into the music. “Why does this sound so much better, Andy?” “It begins with DSP, or Digital Signal Processing.” “You mean things like Auto-Tune that correct people singing off key?” “That’s one application, but a kind of extreme one. Even the simplest devices that record and play sound digital digitally use DSP.” I showed Joe a short list of DSP definitions relating to the everyday audiophile and music enthusiast.

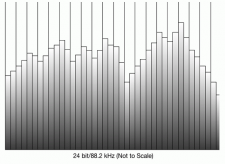

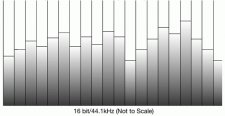

I explained to Joe, briefly, that that the larger the bit depth (16 Vs. 24) and the higher the sampling rate (44.1 Vs. 88.2 or 192 kHz), the more musical information a digital file could hold, and I created a couple of illustrations for him to help drive the point home.

I explained to Joe, briefly, that that the larger the bit depth (16 Vs. 24) and the higher the sampling rate (44.1 Vs. 88.2 or 192 kHz), the more musical information a digital file could hold, and I created a couple of illustrations for him to help drive the point home.

As implied by the simple illustrations, the files with more bit depth and a higher sampling rate have deeper, more frequent slices of music, something called information density, and quite simply carry more information–in the form of numbers–from which to recreate the original analog music waveform.

“You might need to explain in a little more detail, Andy.” “No problem,” I replied. Then our conversation started to take a whole new direction. Next week we will begin to look at DSP more deeply…

“You might need to explain in a little more detail, Andy.” “No problem,” I replied. Then our conversation started to take a whole new direction. Next week we will begin to look at DSP more deeply…