It’s the time of year for saving money!

A trend in home audio towards distributed media servers has stared to evolve. Put simply, a distributed media server adds a computer to your home network on top of an NAS and a streaming DAC that acts as a central point to catalog and index your music files and send them to multiple devices concurrently (at the same same time) controlled from Apps running on mobile phones, tablet computers, of any other computer that you have on your home network. The main advantage to this is that get a lot more processing power to catalog and “serve” the music from one or more NAS’s to one or more streaming DAC’s. Most of the processing related to the music files occurs on the central computer, including decompression and conversion to a common format or protocol that the streaming DAC can easily recognize and place usually with better sound than you can get by having those operations performed by the streaming DAC itself and with greater to access to metadata available on the internet such as cover art and liner notes, plus better access to streaming services such as Spotify or TIDAL [Hi-Fi].

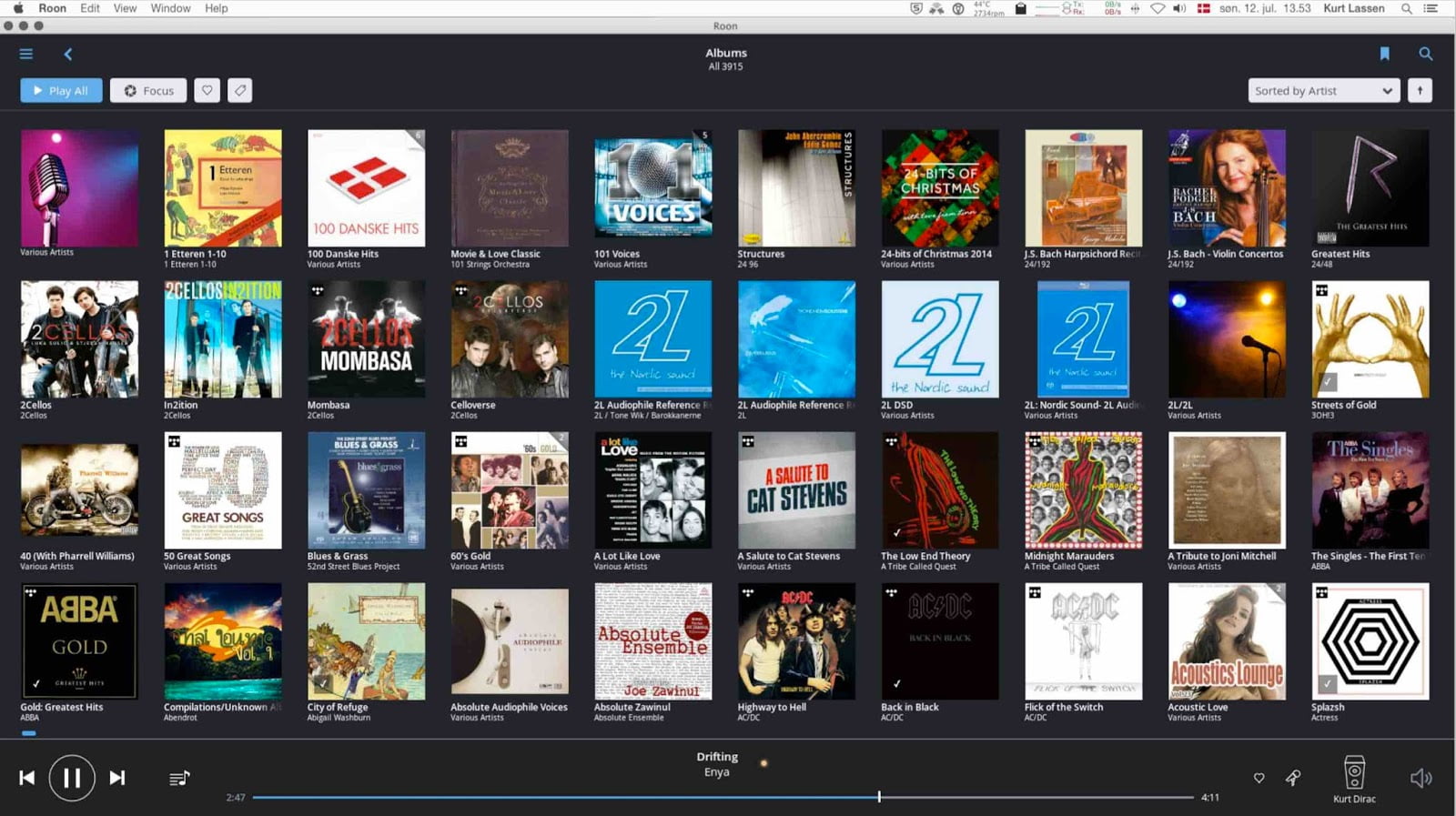

An example of a distributed media server includes Meridian’s Sooloos, also the basis for the Roon system. Roon created a simple API or SDK that can run easily on the most basic “endpoints”, like the Bluesound Node 2, to higher end streaming DAC’s such as the Ayre QX-5 Twenty “digital hub”. In both cases, Roon server runs on either a multipurpose computer, like a MacBook Pro, or, ideally, on a purpose-built server such as the Antipodes DX, which has a built in SSD (Solid State Drive) and automated CD ripper. Designed specifically and only for processing music, the Antipodes could potentially sound better than running the Roon server software on a multipurpose computer, although, strictly speaking, almost any computer running Windows, macOS, or Linux will do. Roon server can easily convert almost any music file format (MP3, AAC, WAV, AIFF, etc.) to a common, relatively jitter-free protocol named RAAT. The server sends all of the music from any source to the streaming DAC using RAAT, which is synchronized to the clock in the streaming DAC, rather working in an asynchronous mode, to further reduce jitter.

An example of a distributed media server includes Meridian’s Sooloos, also the basis for the Roon system. Roon created a simple API or SDK that can run easily on the most basic “endpoints”, like the Bluesound Node 2, to higher end streaming DAC’s such as the Ayre QX-5 Twenty “digital hub”. In both cases, Roon server runs on either a multipurpose computer, like a MacBook Pro, or, ideally, on a purpose-built server such as the Antipodes DX, which has a built in SSD (Solid State Drive) and automated CD ripper. Designed specifically and only for processing music, the Antipodes could potentially sound better than running the Roon server software on a multipurpose computer, although, strictly speaking, almost any computer running Windows, macOS, or Linux will do. Roon server can easily convert almost any music file format (MP3, AAC, WAV, AIFF, etc.) to a common, relatively jitter-free protocol named RAAT. The server sends all of the music from any source to the streaming DAC using RAAT, which is synchronized to the clock in the streaming DAC, rather working in an asynchronous mode, to further reduce jitter.

In my own home network, I store my music on. Melco N1A audiophile-quality NAS mostly in the FLAC format. Almost everything connects through long Ethernet patch cables from AudioQuest. I have two streaming DAC’s, a Bluesound Node 2 in my bedroom connected to a Woo Audio WA6-SE headphone amp and an Ayre QX-5 Twenty in my main, mostly Audio Note system with an OTO Phono SE Signature integrated amp. I run Roon server on a semi-dedicated MacBook Pro and the Roon App on two iPads and an iPhone. I think it all sounds amazing and Roon has a few features that I like, not just TIDAL Hi-Fi integration, but automatic conversion of DSD to PCM files for the Node 2 and something called Roon radio, an automatic, real-time playlist builder that uses the metadata associated with my music collection to keep playing seemingly random tracks in the same musical style and genre as the first album that I select in any one listening session. One planned upgrade includes, probably, an Antipodes DX to replace the MacBook Pro for running Roon server and ripping CD’s.

In my own home network, I store my music on. Melco N1A audiophile-quality NAS mostly in the FLAC format. Almost everything connects through long Ethernet patch cables from AudioQuest. I have two streaming DAC’s, a Bluesound Node 2 in my bedroom connected to a Woo Audio WA6-SE headphone amp and an Ayre QX-5 Twenty in my main, mostly Audio Note system with an OTO Phono SE Signature integrated amp. I run Roon server on a semi-dedicated MacBook Pro and the Roon App on two iPads and an iPhone. I think it all sounds amazing and Roon has a few features that I like, not just TIDAL Hi-Fi integration, but automatic conversion of DSD to PCM files for the Node 2 and something called Roon radio, an automatic, real-time playlist builder that uses the metadata associated with my music collection to keep playing seemingly random tracks in the same musical style and genre as the first album that I select in any one listening session. One planned upgrade includes, probably, an Antipodes DX to replace the MacBook Pro for running Roon server and ripping CD’s.

To briefly revisit the subject of PCM versus DSD, the most common PCM format was the red-book CD with 16-bits sampled at 44.1kHz. DSD recordings were originally commercially available in 1-bit format with a sample rate of 2.8224mHz. This format was used for the SACD and is also called DSD64 because 64 single bits get sampled at a periodic interval such that, if you divide 2,822,400 by 64, you get 44,100 or 44.1kHz, the same general resolution as a red-book, or regular, CD with the same upper analog frequency limit of about 20kHz. You just have to think of the bits as flowing individually side by side with DSD as opposed to getting stacked on top of one another 16 or 24 (or 32) at a time as with PCM. Double DSD and Quad DSD (DSD128 and DSD256) have that much more resolution with no theoretical limit to the dynamic range; however, greater bandwidth and more dynamic range don’t necessarily translate to better sound quality. The devil remains in the details or implementation and having clock speeds that work accurately at millions of samples per second, or MHz, certainly increases the ever-present problems associated with timing or jitter.

To briefly revisit the subject of PCM versus DSD, the most common PCM format was the red-book CD with 16-bits sampled at 44.1kHz. DSD recordings were originally commercially available in 1-bit format with a sample rate of 2.8224mHz. This format was used for the SACD and is also called DSD64 because 64 single bits get sampled at a periodic interval such that, if you divide 2,822,400 by 64, you get 44,100 or 44.1kHz, the same general resolution as a red-book, or regular, CD with the same upper analog frequency limit of about 20kHz. You just have to think of the bits as flowing individually side by side with DSD as opposed to getting stacked on top of one another 16 or 24 (or 32) at a time as with PCM. Double DSD and Quad DSD (DSD128 and DSD256) have that much more resolution with no theoretical limit to the dynamic range; however, greater bandwidth and more dynamic range don’t necessarily translate to better sound quality. The devil remains in the details or implementation and having clock speeds that work accurately at millions of samples per second, or MHz, certainly increases the ever-present problems associated with timing or jitter.

More to come …