It’s the time of year for saving money!

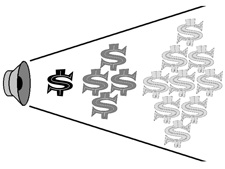

In installments one and two of this three-part article, I wrote about something very much like the Inverse Square Rule that seems to apply to hi-fi performance per dollar spent and makes for a situation where, just as doubling the distance from a source of radiated energy results in quartering the energy level at the doubled distance or halving the distance from the source quadruples the available energy at the shorter distance, the performance level we get for our money when we buy hi-fi gear is less per buck spent when we spend more and disproportionately more when we spend less.

I gave reasons for why this should be the case, and gave examples of it, even in the products of my own former company. In this last installment, I’m going to take a look other factors that influence what we get for our money when we buy our gear and why just spending more money won’t necessarily get us an equal amount more sonic performance.

I gave reasons for why this should be the case, and gave examples of it, even in the products of my own former company. In this last installment, I’m going to take a look other factors that influence what we get for our money when we buy our gear and why just spending more money won’t necessarily get us an equal amount more sonic performance.

A very important one of those factors is simply the idea of “perceived value.” Among my favorite amplifiers of all time (I still own pair of them with all internal wiring upgraded to XLO), is the Model 5 from Jeff Rowland Design Group. These amplifiers have absolutely gorgeous titanium-finished, half-inch-thick aluminum faceplates with huge machined lifting handles (the amps weigh well over 100 pounds each) and the JRDG logo; and with an illuminated “on/standby” switch machined into (instead of bolted onto) them. When, after first getting the amps, I had occasion to compliment Jeff Rowland on their appearance and to comment on the obviously great expense he had devoted to it, Jeff told me that those faceplates and handles had, indeed, been expensive, and that, just in themselves, they had added US$1,000 to the amplifiers’ manufacturer’s suggested retail price (MSRP).

When I asked him why he had chosen to spend so much for something that wouldn’t affect the amplifiers’ performance in any way, he told me that if he hadn’t done so — if he had saved the money and simply put on an ordinary sheet metal faceplate and hardware-store handles — even at US$1,000 less in price, he might not have been able to sell any amplifiers at all!

The fact of it is that even with the cheaper parts, the Model 5s would still have been expensive amplifiers for their day. They would have had to be: That 100-pound-plus weight didn’t consist of just bricks or boat anchors, but of the very best and most costly parts, and a significant part of it was devoted to a HUGE and violently expensive custom-made power transformer (which, because nothing can come out of the amplifier’s output taps that doesn’t first come in through the power-supply section, DID affect the sonic performance). And being expensive, they would have had to look fully as expensive as they were (or, hopefully even more so) in order for people to be willing to buy them.

Jeff Rowland was right: Perceived value plays a very important in our buying decisions, and unless a product looks like it’s worth what the sellers are asking us to pay for it, we may, regardless of its actual performance, pass it by in favor of some other product that looks better at the same price.

(This, incidentally, doesn’t just apply to amplifiers or other hi-fi gear, but to everything we buy. Just as an example, I, for one, can’t imagine ever paying a luxury car price for a vehicle that isn’t expensive-looking! Sure, it doesn’t affect the performance, comfort or reliability of the car, but it certainly affects how I feel about my purchase.)

One of the sad-but-true facts about manufacturing is that making a product look expensive usually adds to its real expense, both to build and to buy. Another is that just the fact of being expensive is likely to make a product even more expensive. It works like this:

One of the basic facts of economics is that that, all other things being equal, the more expensive a thing (any thing at all) is, the less of it will be sold. There are many reasons for this, but here are just a few of them:

1) The more expensive a thing is, the more other expensive things are competing against it for the buyer’s dollar, and some of those other things wind up getting bought, removing those prospective purchase dollars from the available total.

2) Selling a smaller number of goods, the manufacturer will probably not be able to take advantage of economies of scale, and will likely have to pay top dollar for his materials and buy-out services. This will increase his cost and may increase his suggested MSRP to compensate, again reducing the total quantity sold.

3) On custom-made parts from outside suppliers, there may be minimum order quantities that must be bought in order to get the parts made at all. This can mean tying up large amounts of capital in not-immediately-needed inventories, and can increase costs in everything from the increased physical plant area needed to store them to the increased interest cost on borrowed working capital to buy and stock them. This increased cost can also result in increased MSRP and reduced sales.

4) Increased retail price may require increased advertising and promotion expenditures to sell whatever it is, and with fewer units sold, those high promotional costs have to be allocated among fewer units, increasing the per-unit advertising burden, and thus the necessary dealer and retail price to cover it.

5) Because the same “higher-cost-means-fewer-units-sold” axiom applies to dealers, too. Dealers may need to be offered higher wholesale discount percentages in order to entice them to carry the product at all. This will inevitably result in a higher MSRP. (This is particularly common in VERY EXPENSIVE products like super-expensive cables for multi-tens of thousands of dollars or speakers for multi-hundreds of thousands. Without the extra discount, dealers may never stock them, and without them in dealer stock to be displayed and demonstrated, very few or none may ever be sold.)

All of these things and the others that I mentioned in the two earlier installments of this article contribute to why spending twice as much money on your hi-fi system can never be relied on to get you twice as much performance. The other side of it, though, is that, for truly committed audiophiles, ANY improvement may very well be worth whatever it costs as long as it provides a sufficient reward in satisfaction or progress towards their goal.

It’s not for me to judge. What do YOU think?