It’s the time of year for saving money!

What would you think if a review of the latest haza-gaza speaker system included durometer readings for the various elements of its enclosure? Or if amplifiers were performance-rated by weight? Or if audio cables were ranked by their degree of water-resistance?

The truth of it is that people love tests and that practically anything can be tested for a whole lot of things, including some that are utterly irrelevant and some that might be relevant to their performance but that are neither necessarily indicative of it nor the best way to state it. The durometer readings for a speaker enclosure are a good example. These might certainly provide a clue to the enclosure’s rigidity, and thus its ability to flex with or resist the variations in internal air pressure resulting from the movement of its drivers’ diaphragms. Enclosure flexure (resonance) is undeniably a possible contributor to the sound of the system, but aren’t there other, more significant things that could be tested to gain an understanding of its sound quality? Similarly, for at least some kinds of amplifiers, what they weigh really can be an indicator of sound quality (More weight is likely to indicate bigger transformers – either power, output, or both) and bigger transformers may very well be both better and better-sounding than smaller ones, and might very well make for a better-sounding amplifier. But why not use some more direct test of performance.

The truth of it is that people love tests and that practically anything can be tested for a whole lot of things, including some that are utterly irrelevant and some that might be relevant to their performance but that are neither necessarily indicative of it nor the best way to state it. The durometer readings for a speaker enclosure are a good example. These might certainly provide a clue to the enclosure’s rigidity, and thus its ability to flex with or resist the variations in internal air pressure resulting from the movement of its drivers’ diaphragms. Enclosure flexure (resonance) is undeniably a possible contributor to the sound of the system, but aren’t there other, more significant things that could be tested to gain an understanding of its sound quality? Similarly, for at least some kinds of amplifiers, what they weigh really can be an indicator of sound quality (More weight is likely to indicate bigger transformers – either power, output, or both) and bigger transformers may very well be both better and better-sounding than smaller ones, and might very well make for a better-sounding amplifier. But why not use some more direct test of performance.

It’s the same thing for water-resistance in cables: The sonic difference from making water a part of a cable’s dielectric, either by immersing the cable in water or by making the water a part of the cable, itself, was proven decades ago by Jim Aud’s Purist Audio Design. The water does change the sound of the cable, but so what? Making practically anything a part of the dielectric will change a cable’s sound, but as to whether the change is for the better or worse depends on what that “anything” might be; what the rest of the cable’s design is; and the tastes and preferences of the listener. And of course, water resistance can be important in other ways than just a cable’s sound: If, as with Jim Aud’s cables, the water is on the inside, you want it to stay there and not get out, either by leakage or evaporation. And as for water outside the cable, you certainly want to keep it outside, where it can’t create short circuits, corrosion, or other damage.

As both a long-time Hi-Fi Crazy and a member of the audio press – and particularly as a former cable manufacturer (XLO) – I constantly run across people who won’t believe anything about Hi-Fi gear (not even as heard by their own ears or reviewed by a major publication or industry “expert”) unless it’s accompanied by a set of numbers (measurements or test data) that they can take as gospel.

As both a long-time Hi-Fi Crazy and a member of the audio press – and particularly as a former cable manufacturer (XLO) – I constantly run across people who won’t believe anything about Hi-Fi gear (not even as heard by their own ears or reviewed by a major publication or industry “expert”) unless it’s accompanied by a set of numbers (measurements or test data) that they can take as gospel.

I have no problem at all with numbers: As a manufacturer, I used them all the time, for whatever benefit they could provide. There were problems, though, and they were manifold: For one thing, which things should be measured? What if two things measure the same but sound different? What if two things sound the same, but measure different? What if some measured information is simply meaningless or inapplicable?

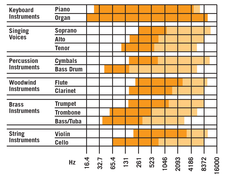

In times past, and even now, frequency response was one of the standard measurements for audio gear, stating that a piece of gear would produce sound or signal from some frequency to some other frequency, usually within a deviance of plus or minus 3 decibels (“dB”). That’s all well and good, but what exactly does it mean? Three decibels makes for a loudness difference of half or twice, depending on whether you’re talking 3 dB up (+3dB) or 3 dB down (-3dB). That makes for a total range of 6dB, or 4 times louder or quieter than the reference level, whichever the case may be — obviously quite a significant difference. Now, consider three hypothetical audio products: All have a 20Hz to 20,000Hz frequency range, but #1 is “flat” (measures on the “zero line”) at 20Hz, is up 3db at 40Hz, one octave later, is down 3dB at 80Hz, the next octave point, and continues being up 3dB or down 3dB at each octave point (doubling of frequency) throughout the full frequency spectrum. #2 measures “flat” (exactly on the zero line) at every point from 20-20,000Hz, except for a very narrow 6dB “peak” centered at 1.5kHz, right smack in the middle of the human ear’s greatest sensitivity range. And product #3 is exactly the opposite, being flat at every point from 20-20,000 Hz, except for a very narrow 6dB “notch” at 1.5kHz. All three products conform exactly with the “plus or minus 3dB (+/- 3dB) specification, but the three will likely sound wildly different.

So is that defined frequency response “spec” any more useful in trying to anticipate what the product will sound like than the old trick that some manufacturers of cheap car audio or lo-fi home stereo used to do by just saying that their stuff would produce sound from “20 to 20,000Hz” without either giving any range of variance at all or telling you that, yes, it will do 20hz, but at that frequency it will be down 40db and completely inaudible?

So is that defined frequency response “spec” any more useful in trying to anticipate what the product will sound like than the old trick that some manufacturers of cheap car audio or lo-fi home stereo used to do by just saying that their stuff would produce sound from “20 to 20,000Hz” without either giving any range of variance at all or telling you that, yes, it will do 20hz, but at that frequency it will be down 40db and completely inaudible?

I don’t think so, and it reminds me of something that happened when I was in my teens, and actually had a (very) little money to spend on good speakers: RCA’s professional products division, RCA Broadcast Audio, had an office in Hollywood at that time and, hearing that the RCA LC-1a speakers, designed by Dr. Harry Olson, were very good, I called the company and asked about them (this must have been after 1957, because stereo, as I remember, was already starting to become popular). The sales engineer I spoke with was very kind and, when I asked for a spec sheet, he asked me if I knew how to read one, to which I (who at that time knew everything and was insulted to think that anyone might doubt it) told him that of course I did, to which he replied something like “Good, because these sound great, but don’t look like much on paper”, and promised to send me the entire RCA Broadcast Audio catalog.

When that came and I looked-up the LC-1a, I saw that the engineer had been right; the frequency response curve published for it was nothing like as flat as I had hoped for; and I dismissed the speakers from further consideration. Then, in 1963 or ’64, when I went to the brand-new Cinerama Dome in Hollywood for the first time, and heard what was without doubt the very best sound I had ever heard in a movie theater, and somebody told me that the whole stereophonic sound system for the dome had been done using RCA LC-1a’s, it occurred to me that maybe I didn’t know how to read frequency response curves after all. Or, that maybe just looking at a curve wasn’t really the best way to learn what a thing sounds like.

When that came and I looked-up the LC-1a, I saw that the engineer had been right; the frequency response curve published for it was nothing like as flat as I had hoped for; and I dismissed the speakers from further consideration. Then, in 1963 or ’64, when I went to the brand-new Cinerama Dome in Hollywood for the first time, and heard what was without doubt the very best sound I had ever heard in a movie theater, and somebody told me that the whole stereophonic sound system for the dome had been done using RCA LC-1a’s, it occurred to me that maybe I didn’t know how to read frequency response curves after all. Or, that maybe just looking at a curve wasn’t really the best way to learn what a thing sounds like.

More on testing and what it means in part 2. For now, though, I’m out of space.

See you next time.