It’s the time of year for saving money!

I ended Part 11 of this series of articles about phonograph records and the equipment for playing them by bringing up the tonearm and how it affects not only the playing, but also the actual cutting of records…

Historically, two approaches have been taken to the problem of how to hold the cartridge so that the “needle” (Nowadays, we call it the “stylus”) will be properly positioned to either cut or play back a record. The first, that came-in with the very first cylindrical recordings – whether on foil or, later, wax or other materials – was “transverse”, meaning, in this case, “across the record, at a constant angle”. Starting in the late 1880s disc records – the format we are now more familiar with, became available and, after 1912, dominant, and with them came the possibility of the “radial” tonearm which, instead of moving the cartridge across the record in a line, maintaining a constant angle to the groove, tracked it in an arc, from a single pivot point.

Historically, two approaches have been taken to the problem of how to hold the cartridge so that the “needle” (Nowadays, we call it the “stylus”) will be properly positioned to either cut or play back a record. The first, that came-in with the very first cylindrical recordings – whether on foil or, later, wax or other materials – was “transverse”, meaning, in this case, “across the record, at a constant angle”. Starting in the late 1880s disc records – the format we are now more familiar with, became available and, after 1912, dominant, and with them came the possibility of the “radial” tonearm which, instead of moving the cartridge across the record in a line, maintaining a constant angle to the groove, tracked it in an arc, from a single pivot point.

If you remember that the term “cutting a record” actually meant cutting a record, it’s easy to understand why those first “tonearms” were transverse: Whether for a cylinder or a disc, they were the easiest way to do what was necessary – first, to actually cut a track in the medium, and then to play it back. In the cutting mode, the record cutting machine acted as, and was actually called a “lathe”, and the function of the “arm” portion of it was to set the cutting stylus to a desired mean depth of groove (the earliest recordings were vertically – up-and-down or in-and-out — instead of side-to-side modulated, as later became the norm); to hold it there; and, with the cylinder or the disc turning, use a leadscrew to move the cartridge (called the “cutting head”) across the medium to make the groove. All of the early recordings – in fact, until “DynaGroove” or its equivalents came along in the 1960s- used constant groove spacing, most easily provided by a leadscrew turning at constant speed.

As to playback, for cylinders, the playback tonearm also had, simply because of the shape of the record it was playing, to be transverse and had all of the problems of the transverse tonearm that I will be writing about in later installments. It compensated for them, though, with very high tracking force (sometimes in the ounces) that simply overwhelmed them. For discs, the easiest (read “cheapest”) way to hold the cartridge for playback was to use a radial arm (think about the RCA dog picture, with Nipper sitting next to a radial armed gramophone with the horn directly attached to the arm, listening to His Master’s Voice) and that was how most disc players were presented to the consumer market.

As to playback, for cylinders, the playback tonearm also had, simply because of the shape of the record it was playing, to be transverse and had all of the problems of the transverse tonearm that I will be writing about in later installments. It compensated for them, though, with very high tracking force (sometimes in the ounces) that simply overwhelmed them. For discs, the easiest (read “cheapest”) way to hold the cartridge for playback was to use a radial arm (think about the RCA dog picture, with Nipper sitting next to a radial armed gramophone with the horn directly attached to the arm, listening to His Master’s Voice) and that was how most disc players were presented to the consumer market.

In the early, low- or no-fi, days, the simple fact that sound was coming out of a machine was sufficient for most people, and the reality that the sound was what we would now consider awful was, for lack of comparison, of little consequence. Neither was the fact that records would wear out after all too few playings. Listeners of the time were, in general, too amazed by the fact of the music or other recorded content to even notice such other things.

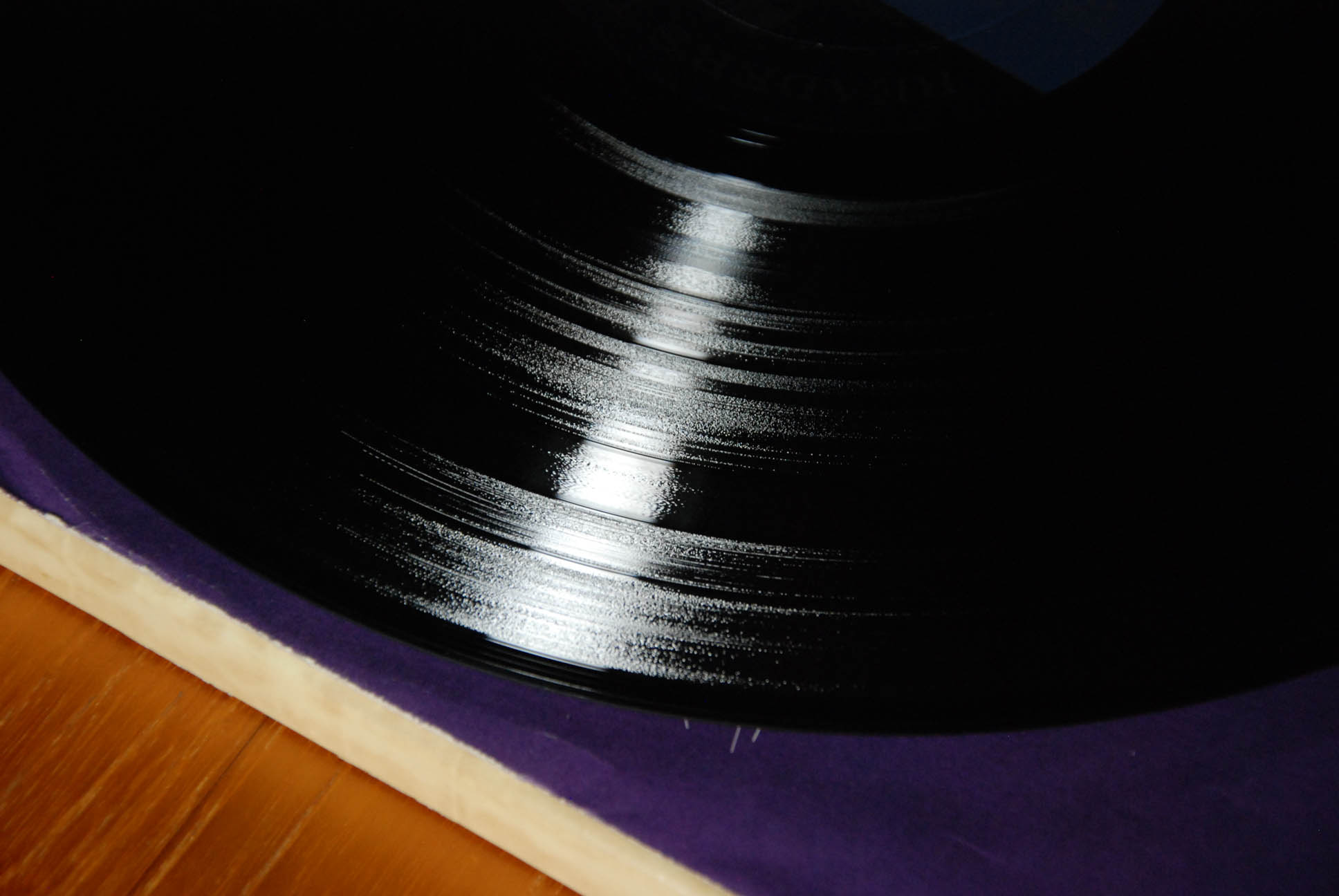

The fact, though, was that there was always an underlying problem: Records cut on a transverse lathe would always suffer “tracking error” and its corresponding distortion when played back using a radial tonearm. The reason was simplicity, itself: With a transverse arm, either for cutting or playback, the cartridge, and therefore the stylus is always – because it is tracking in a straight line – at precisely the right angle in relation to the groove and can, therefore, play back the groove at precisely the angle at which it was cut. With a radial arm, though, the cartridge swings across the record in an arc, constantly changing its angle in relation to the groove and only at one point being at exactly the correct angle.

This results in error and distortion which, granted, on the very best radial tonearms today is minimal, but, even on them, is still there. (At least one radial tonearm, the B-J “tangential” arm from England [and perhaps the Garrard Zero 100, too] managed to overcome this problem by using a pantographic design to maintain, even despite its radial construction, a constant tracking angle. This design had its own problems, however, and the B-J arm was never a success.)

This results in error and distortion which, granted, on the very best radial tonearms today is minimal, but, even on them, is still there. (At least one radial tonearm, the B-J “tangential” arm from England [and perhaps the Garrard Zero 100, too] managed to overcome this problem by using a pantographic design to maintain, even despite its radial construction, a constant tracking angle. This design had its own problems, however, and the B-J arm was never a success.)

But, if most of the world’s record-players have radial tonearms, why isn’t it possible to cut a record with a radial-armed lathe?

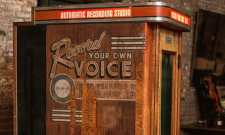

In fact, during World War II, there was a great desire for those still at home to be able to communicate with their loved ones fighting overseas, even if only to send a message of love and support. To that end “Record Your Voice” booths popped up everywhere, and in them, for a few coins, you could cut your own brief record to send it to whomever you wished. I don’t know how those booth machines worked, but the principal of cut-your-own recordings came home for private use, as well. Silvertone, and perhaps other manufacturers, as well, had home radio/phono combinations that, in addition to playing records, would actually record them. I know, because when I was young, I owned and used one that, as a kid Hi-Fi Crazy, had been handed-down to me by my family.

To cut records on this machine, you used “blank” discs available at Sears and at local record stores, and, putting one of those on the platter, you raised the arm at its pivot, which caused the arm’s sub-structure to lock into a leadscrew inside the plinth (actually a moderate-sized suitcase). Lifting the back of the arm also caused a spring-tab to lock into position, to force the cartridge-end of the arm downward to provide cutting pressure. Then, using the same crystal cartridge that was used for playback, but changing to a special cutting needle, you could, by flipping a selector switch, either record the spoke voice, singing, or musical messages using the unit’s included microphone or record directly from the radio.

To cut records on this machine, you used “blank” discs available at Sears and at local record stores, and, putting one of those on the platter, you raised the arm at its pivot, which caused the arm’s sub-structure to lock into a leadscrew inside the plinth (actually a moderate-sized suitcase). Lifting the back of the arm also caused a spring-tab to lock into position, to force the cartridge-end of the arm downward to provide cutting pressure. Then, using the same crystal cartridge that was used for playback, but changing to a special cutting needle, you could, by flipping a selector switch, either record the spoke voice, singing, or musical messages using the unit’s included microphone or record directly from the radio.

Not great, or even adequate by current standards, but it worked, and people by the thousands bought them to send messages, communicate with friends or loved ones, or memorialize baby’s first burp.

So, it IS possible to record using a radial “lathe” and to get tracking-error-free playback from your own home radial-arm record player. All that’s necessary is for somebody to actually make an audiophile-quality radial-arm cutting lathe, and that may already be in process: Jeremy Kipnis, recording engineer; scion of harpsichordist, Igor Kipnis; grandson of Metropolitan Opera basso, Alexander Kipnis; and owner of Epiphany Recordings, Ltd., is interested and has spoken with the folks at VPI (turntables) and others about the possibility of building such a thing for professional studio use and, the last I heard, he was intent on going forward with it.

So, it IS possible to record using a radial “lathe” and to get tracking-error-free playback from your own home radial-arm record player. All that’s necessary is for somebody to actually make an audiophile-quality radial-arm cutting lathe, and that may already be in process: Jeremy Kipnis, recording engineer; scion of harpsichordist, Igor Kipnis; grandson of Metropolitan Opera basso, Alexander Kipnis; and owner of Epiphany Recordings, Ltd., is interested and has spoken with the folks at VPI (turntables) and others about the possibility of building such a thing for professional studio use and, the last I heard, he was intent on going forward with it.

Who knows, Epiphany Recordings are already good-sounding, and may soon be the only ones to offer error-free playback on most conventional record-players. I can hardly wait.

In the meantime, there’s till the issue of which is better — a transverse arm or a radial one? I’ll go more into that next time.

See you then.

Other articles by Roger Skoff can be found at Enjoy the Music