It’s the time of year for saving money!

The main goal of audio fidelity is to get as close as possible to

the original recorded event. Anything that distances the listener further away from

the event reduces fidelity. In the analog world each and every added

generation, be it from multi-track to two-track master or master to stamper to

pressed LP disc, reduces the final fidelity of a recording. In the digital

world, although we have “bit-perfect” transfers from one generation to the

next, conversions from the native rate, or from one digital format to another,

like generations in analog, does lower a music file’s final fidelity. The

ultimate example of this would be going from a 192/24 full-resolution file to

128 KBPS MP3.

In the old days we had the term “master tape” which, depending

on how they were made, could themselves be two or three generations away from

the original recorded multi-track taped event. Companies like Opus 3, whose

early recordings were primarily live to two-track, had a sonic advantage

because they didn’t need mix-downs from multi-track to two-track. The two-track

original WAS the master. That got their listeners one generation closer to the

musical event.

The purest form of analog recording, direct to disc, where the

mixing board feeds a cutting lathe, so instead of tape-to-master, the master is

cut directly, sounds so good because it eliminates at least three generations

from the analog reproduction chain. The digital equivalent would be a live

recording done at 192/24 or DSD that is played back in the native format that

it was made in. In both cases there is one big creative problem – no editing or

retakes are possible. Obviously if everyone plays their parts perfectly the

one-take, no-editing methodology dictated by the process isn’t a problem. But

for most musicians knowing that there will be no retakes means they will pick

the safest way to play a passage, which may not be the most musically

adventurous or exciting way. Perhaps this is why many direct-to-disk recordings

are not very exhilarating or passionate – the process works against it.

Obviously, your average MP3 music consumer has no idea what a

master tape sounds like. But even among audiophiles, far too few audiophiles

have heard master tapes. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons so many of us go

gaga every time we are presented with a new format that gets us closer to the sound

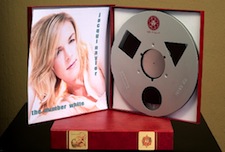

of the master tape. Analog enthusiasts have been raving over the new subscription

tape series from The Tape Project ever since their first tape was released. Why? Because releasing in the tape

format bypasses all the LP-manufacturing steps, which reduce fidelity and

distance the listener from the original musical event. It should come as no

surprise that the Tape Project releases sound better than the original LPs. The

really big surprise would be if any of them sounded worse.

J. Gordon Holt always preferred listening to a 7½ IPS tape over

a record if he had a choice. And his reason wasn’t because the LPs always

sounded bad, but because the tapes were always closer to the original musical

event, and getting back to the moment of creation is what high-fidelity is all

about.

When I first became interested in high end audio, some forty years ago now, most of the “better” systems had a turntable but also included a reel to reel. As is well known, vinyl sort of became a recluse, cassettes gave way to CD’s and vinyl has once again popped it’s head out. Personally, I would love to add a reel to reel into my reference system. The availability of tapes are, at least for now, so woefully inadequate that it hardly makes the cost of a deck practical. Right now, I have a fantastic CD store with a surprisingly good vinyl section that is ten minutes away from my home. I can purchase all sorts of standard resolution CD’s from companies like Amazon. There are a number of catalog and Internet suppliers of all sorts of vinyl. Then there are the sites like HD Tracks where I can download high resolution digital files. All told, I have a multitude of sources for digital and vinyl and have excellent availability of any music type in which I am interested. With only one well known source for reel to reel tapes, the Tape Project can hardly be considered a source for a wide variety of music. I do understand the crawl before you walk aspect of this music format and I expect it to continue to grow. Frankly, I’d love to see a proliferation of manufacturers of decks and better availability of high quality pre-recorded tapes. When that day comes, more audiophiles will take the plunge into the ultimate medium of sound reproduction. And I’ll be at or near the front of the line.

Decent reel to reels are available quite inexpensively – just leave a few bucks in your pocket to address any outstanding issues or upgrades and you can get a very high end deck quite reasonably.

MP3 is garbage! I like AIF, it uses loss less compression and is CD quality. Files are much bigger but so what? HDs are cheap and huge in size and so are memory cards. Just about everyone has high speed internet these days so what’s the point of staying with MP3? For me it’s all about sound quality.

The author states “In both cases there is one big creative problem- no editing or retakes are possible” inferring that DSD and 192kHz digital have the same problem as direct-to-disk recording. DSD and any PCM digital format can easily be edited on a workstation, I”m not sure what he meant to day.

I can’t see why master tape to digital transfer wouldn’t sound at least as good as master tape to Tape Project tape transfer. This project sounds to my just like another ruse to make profit on people’s nostalgia for “good old days”