It’s the time of year for saving money!

If I remember correctly, it was Joe Grado who came up with the first stereo moving-coil phono cartridge. And, if I remember correctly about this, too, it was also he who (at least at the very beginning) stated outright that he never expected it to amount to much.

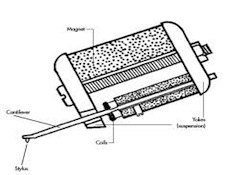

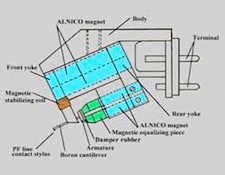

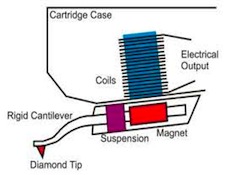

Stereo moving-coil cartridges work, just as the name implies, by moving a pair of coils (one for the right channel and one for the left) within a magnetic field to break the field’s magnetic lines of force and produce a voltage, which gets sent off to the system’s electronics to be amplified and ultimately to come out of its speakers as music. The magnet(s) is/are inside the body of the cartridge and the coils are mounted to the cartridge’s cantilever either before or, more usually, after the cantilever’s pivot, which is some distance behind the stylus, which is also mounted to the cantilever. When the stylus is dragged through a record’s groove, it’s caused to move back-and-forth and up-and-down; which moves the cantilever on its pivot; which causes the coils to move in the same patterns as the stylus (although backwards, if the stylus and the coils are, as they usually are, on opposite ends of the cantilever); which breaks lines-of-force; which produces a signal voltage; and so on.

Stereo moving-coil cartridges work, just as the name implies, by moving a pair of coils (one for the right channel and one for the left) within a magnetic field to break the field’s magnetic lines of force and produce a voltage, which gets sent off to the system’s electronics to be amplified and ultimately to come out of its speakers as music. The magnet(s) is/are inside the body of the cartridge and the coils are mounted to the cartridge’s cantilever either before or, more usually, after the cantilever’s pivot, which is some distance behind the stylus, which is also mounted to the cantilever. When the stylus is dragged through a record’s groove, it’s caused to move back-and-forth and up-and-down; which moves the cantilever on its pivot; which causes the coils to move in the same patterns as the stylus (although backwards, if the stylus and the coils are, as they usually are, on opposite ends of the cantilever); which breaks lines-of-force; which produces a signal voltage; and so on.

Among the reasons that Grado may have had for not putting too much faith in the moving-coil design is that it’s got some potentially serious problems regarding mass and output. The physically smaller the coils are, and the fewer the number of turns in their windings, the lower the output of any moving-coil cartridge will be, and the more amplification it will require to make its output usable. Except with the very finest electronics, very low output can be a problem, but so can its solution — a bigger set of coils with a greater number of turns.

The bigger the coils are, the greater the output will be, but so also will be the potential for problems related to moving mass and resonance. Because of resonance issues arising from both the mass and the positioning of the coils and the necessary length of the cantilever to accommodate them, many of even the very best moving coil cartridges have had a distinct and clearly audible rise in their response at high frequencies, and often ultrasonic peaks in the range of 30 to 50 kHz. Having TWO coils, angled at ninety degrees to each other, to pick up the motions of the two stereo channels, also doubles moving coil mass as compared to a monophonic system and can have an effect on the compliance and tracking ability of the cartridge and complicate its internal design.

The bigger the coils are, the greater the output will be, but so also will be the potential for problems related to moving mass and resonance. Because of resonance issues arising from both the mass and the positioning of the coils and the necessary length of the cantilever to accommodate them, many of even the very best moving coil cartridges have had a distinct and clearly audible rise in their response at high frequencies, and often ultrasonic peaks in the range of 30 to 50 kHz. Having TWO coils, angled at ninety degrees to each other, to pick up the motions of the two stereo channels, also doubles moving coil mass as compared to a monophonic system and can have an effect on the compliance and tracking ability of the cartridge and complicate its internal design.

Interestingly, some people think that it may have been the characteristic high frequency rise of moving coil cartridges that, by enhancing the apparent clarity, imaging, and soundstaging of recordings played using them has contributed to their very great popularity for high-end-audio LP playback, especially when used in conjunction with tubed electronics.

Whether or not their frequency-response works to their benefit, one thing about most moving coil cartridges that’s NOT an asset is their output level. In the OLD, old days of playing-back phonograph records electronically, the cartridges that were used were made with Rochelle salt, a piezoelectric crystal that, when bent or compressed, produced a voltage – in some cases, as much as two full volts — and, because their naturally rolled-off frequency-response was a fair complement to the high-frequency “boost” that records were recorded with, required little or no playback equalization. Those “crystal” cartridges were first replaced by ceramic cartridges that worked on a similar principal, but were cheaper and easier to make and, though their output was less, was still quite sufficient to drive an amplifier without help or equalization. Next along came the magnetic cartridges – specifically, the trend-setting “Variable Reluctance” cartridge by General Electric, which while it offered a whole host of advantages, including better sound and greatly extended record life, was VASTLY lower in output (at around 10 millivolts, its output was less than 1/100th that of earlier crystal or ceramic models), and had to be amplified and equalized before it could drive the amplifier that would eventually get its output up to speaker-level. (Hence the need for a “pre-amplifier”, which when it first came along was just a simple one-tube device for equalizing the few millivolts of output of a low output magnetic cartridge and bringing it up to a level (line-level, or the equivalent of about one volt), where it could be fed to an amplifier to drive a speaker (Remember that this was all still back in the mono era).

From the simple “pre-amplifier” it was not too long a step to get to the modern “preamp” – a multi-stage, multi-function device descended from it, that includes, at the very least, one or more low-level phono inputs; one or more line-level inputs; an input selector switch; a volume control; and probably (unless there are two separate volume controls) a “balance” control for making sure that the output levels to the “main” amplifier sound the same for both channels.

From the simple “pre-amplifier” it was not too long a step to get to the modern “preamp” – a multi-stage, multi-function device descended from it, that includes, at the very least, one or more low-level phono inputs; one or more line-level inputs; an input selector switch; a volume control; and probably (unless there are two separate volume controls) a “balance” control for making sure that the output levels to the “main” amplifier sound the same for both channels.

Whereas the initial one-tube pre-amplifiers offered anything from about 12 to about 20 dB of gain, modern preamps feature gain of as much 80 dB, and offer cartridge “loading” — resistive and sometimes even capacitive — at a broad range of values. This is necessary because, unlike current moving magnet or moving iron cartridges, which all tend to have multi-millivolt outputs and seem all to call for a load impedance of 47k, moving coil cartridges vary WIDELY in output – all low, but surprisingly many with outputs as little as 0.1 millivolt (TWO ORDERS OF MAGNITUDE BELOW THE EARLIER G.E. MAGNETICS) – and can require resistive loading as little as just a few Ohms and, in some cases or with some phono cables, capacitance values so wildly ranging that some preamps actually provide a slot for wiring-in a capacitor of whatever value you may choose.

What this has done is several things – some of them technologically thrilling; many of them producing genuinely better sound and greater enjoyment of our hobby; but not all resulting in anything like “more bang for our Hi-Fi buck”.

]]> For one thing, it has resulted – by sheer concentration for at least the last 30 years – in the development of the moving coil cartridge to the point where it’s probably as good as it’s ever going to get. Just about everything that has given even the slightest indication of possible improvement, from overall design to the design and materials for each of the component parts has been tried by some manufacturer, and what has worked has been kept and used for even further attempts at improvement.

For one thing, it has resulted – by sheer concentration for at least the last 30 years – in the development of the moving coil cartridge to the point where it’s probably as good as it’s ever going to get. Just about everything that has given even the slightest indication of possible improvement, from overall design to the design and materials for each of the component parts has been tried by some manufacturer, and what has worked has been kept and used for even further attempts at improvement.

Another benefit is that the modern preamp has developed to the point where even cartridges (like the Ikeda, some of the early Ortofons, the Miyabi, and others) that would, in times past, have been considered – no matter how good-sounding — simply too low in output to ever be usable, can now be handled with relative ease…and even with a good signal-to-noise ratio.

One of the problems is that this, whether in the building of the cartridge or the preamp to play it through, has resulted in vast complexity and the need for ultra-specialized components and exquisitely skilled craftspeople, and has made the best of both the cartridges and the preamps so viciously expensive that, even as they get better and better, fewer and fewer people can afford them.

Another problem is that, in HiFi as in everything else, Murphy’s Law applies: “Anything that CAN go wrong WILL go wrong.” Even when the finest designers use the finest materials, every time something – the signal from a phono cartridge, for example – gets touched or processed or conveyed or passed through any component or stage of electronics, the opportunity is there for distortion or for adding something that shouldn’t be there or taking away something that should. Low output or the need for critical loading always means more operating stages and more operating stages always makes for the possibility of more things going wrong.

Perhaps it’s time to take another look at moving magnet or moving iron cartridges, or strain gauges, or any of the other cartridge formats and operating mechanisms that HAVEN’T been so well developed in the last many years and see if there are opportunities there for both the higher output that we already know those designs to be capable of AND better performance. That could make for both better and cheaper cartridges and – who knows what wonders and glories might be possible to modern technology using the very latest of modern materials — maybe even cheaper great preamps or (fanfare!) a return to the days when high enough output made it possible to use either just a “passive” preamp, like those popular some years ago or (Wonders and Glories!) no preamp at all!

Wouldn’t THAT be great; not only for new toys and goodies for us, but to attract budget-conscious young, new audiophiles to come help play and to enjoy our hobby?

Hey, all you sharp guys out there! You can make it happen! Do it!

Another problem is that, in HiFi as in everything else, Murphy’s Law applies: “Anything that CAN go wrong WILL go wrong.” Even when the finest designers use the finest materials, every time something – the signal from a phono cartridge, for example – gets touched or processed or conveyed or passed through any component or stage of electronics, the opportunity is there for distortion or for adding something that shouldn’t be there or taking away something that should. Low output or the need for critical loading always means more operating stages and more operating stages always makes for the possibility of more things going wrong.

Perhaps it’s time to take another look at moving magnet or moving iron cartridges, or strain gauges, or any of the other cartridge formats and operating mechanisms that HAVEN’T been so well developed in the last many years and see if there are opportunities there for both the higher output that we already know those designs to be capable of AND better performance. That could make for both better and cheaper cartridges and – who knows what wonders and glories might be possible to modern technology using the very latest of modern materials — maybe even cheaper great preamps or (fanfare!) a return to the days when high enough output made it possible to use either just a “passive” preamp, like those popular some years ago or (Wonders and Glories!) no preamp at all!

Wouldn’t THAT be great; not only for new toys and goodies for us, but to attract budget-conscious young, new audiophiles to come help play and to enjoy our hobby?

Hey, all you sharp guys out there! You can make it happen! Do it!