It’s the time of year for saving money!

Did you ever wonder how a tiny little signal – like from an

Ikeda or one of those other absurdly low-output phono cartridges – can get to

be big enough to shake the walls of your listening room? Or why tubes have that

pretty glow? Or what the difference is between an amplifier, a preamp, and a

pre-preamp? Or between tubes and transistors? If you’re not a pro or an

engineer or otherwise already “in the know”, the answers may surprise you:

They’re not what common sense might lead you to expect.

In writing this article, I’m going to answer those questions,

and I’m going to do it in the simplest possible terms and language. That means

that not only will I leave out important details, but that virtually ALL detail

will be left out, and that what’s left will be stated in a way that I hope will

be helpful to the average interested audiophile. (TROLLS TAKE NOTE: I’M DOING

IT ON PURPOSE!) In writing about tubes, only the very simplest (triodes) will

be described, and only in the very simplest way. Same thing with transistors;

only “junction” type, the most basic form will ever be mentioned. More complex

and sophisticated elaborations of both devices certainly do exist, but, whether

the most basic or the most refined, they all operate on the same principles and

those are what I hope to convey here.

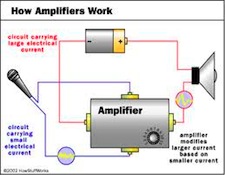

The key to everything is the fact that amplifiers don’t

amplify! They DON’T take that tiny signal and make it big enough to destroy, if

not the world, at least your eardrums and your peace with your neighbors! What

they do, instead, is to use the small signal (from your cartridge, your other

source, or your preamp or other intermediate stage) to modulate an

already big flow of electrical energy so that that larger flow can be used to

drive whatever (speakers, headphones, another component) is the next step up

the line.

If you’ll think of tubes or transistors — the things commonly

called amplifying devices – not as amplifiers at all, but as gates allowing

varying passage to a constant flow of people or as faucets controlling the

constant pressure of water already in your pipes, you’ll have no trouble

understanding how these things operate.

The English call tubes

“valves” because that’s precisely how they work: All tubes have at least three

working elements, the cathode (negatively charged), which is a source of

electrons; the anode (positively charged) which is what those electrons want to

flow to; and the grid, which is the “gate” or “faucet” to control the

flow. These three things are enclosed in

a fourth, non-functional, element – a glass envelope which holds all the parts

and a vacuum which facilitates electron flow and keeps things from burning up.

Heating the cathode (either by applying current to it directly or by having a

separate filament [“heater”]) causes electrons to be available to jump the

physical distance from the cathode to the anode which attracts them. (It’s the

heating of the cathode that cause that lovely glow) Between the cathode and the

anode (the “plate”) is the grid, which when charged with the alternating

current of an audio (or whatever) input signal constantly changes polarity and

charge intensity in accordance with the polarity and amplitude of that signal

(the “gatekeeper”) and either more or less blocks (if it’s negative) or more or

less helps (if it’s positive) to attract the electrons from the cathode to the

plate.

The result is that the grid, by allowing more or less current

to flow in a pattern corresponding to the pattern of the input signal, causes

the large current flow from cathode to plate to become a larger image of the

input signal that controls its creation, and it’s that larger image and not any

“somehow-made-bigger” original input signal that becomes the amplifier’s output

to the next step of the System. The “gain” of an “amplifying” device (an

“amplifier stage” or “gain stage”) is nothing more than the difference in

“size” (amplitude, current flow, or voltage) between the input signal and the

output signal that’s controlled by and substituted for it.

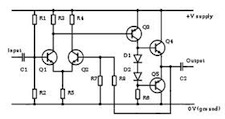

With transistors the process is exactly the same, with the

transistor’s three elements – the emitter, the base, and the collector

(corresponding, respectively, to the cathode, grid, and plate of a triode tube)

modulating the large dc current available from the power supply capacitors of

any solid-state amplifier.

In fact, the only difference between the basic “amplifying”

process in tube and solid-state devices is that tubes use heat to make their

own current for modulation by the source signal and transistors get all of

their current-to-be-modulated from the amplifier’s power supply capacitors.

(HINT: That’s why bypassing the power supply caps with premium smaller ones can

make a significant improvement to solid-state sound)

The one thing that I haven’t covered yet is that when the big

current is “shaped” by the little one, even though it’s identical in form, it’s

180 degrees out of phase. That’s because a negative charge at the grid or base

will BLOCK negative flow from the cathode or the capacitors, and vice versa

(Remember that opposite charges attract and similar charges repel each other)

with the result that the polarity of the output is always opposite that of the

input.

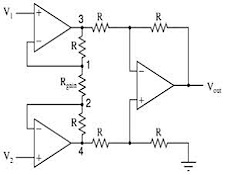

Because of that phase (polarity) shift and also because, with

different loading, different amounts of gain can be had, most amplifiers,

whether tube or solid state use more than just one gain stage. It could simply

be that one “unity-gain” (zero increase) stage is added to a higher gain

“amplifying” stage to restore the original phase of the input signal, or it

could be that, for high output (to drive speakers, for example) or some other

purpose (control or equalization) multiple gain stages are used, either in

series, or in paralleled series-pairs. That’s part of the answer to the

question about the difference between an amplifier and a preamp or pre-preamp:

Other than the number of gain stages and whatever control or equalization

functions may be built-in, there is NO difference at all between any of those

components: They all use exactly the same process to control one flow of

electrons with another and then substitute the controlled flow for the original

one.

Whether

tube or solid state, high gain or no gain, the simplest single stage or the

wildest array of multiple stages, it’s always the same thing: amplifiers don’t

amplify!

So lets call them modulators then ?.

Great article and explanation of why many amplifier companies put so much effort into their power-supplies. ASR has two or three out-board power-supplies; the one for the pre-amp stage of their integrated amp are batteries – pure DC. A few phono-stages utilize batteries for the lowest noise. This also explains the obsession with power conditioners. Would love a course on the good, the bad and the ugly of how power conditioners work with all of the variations.