It’s the time of year for saving money!

When I first got into HiFi, things were different. For one

When I first got into HiFi, things were different. For one

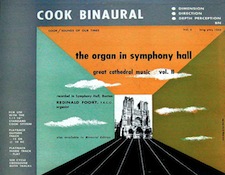

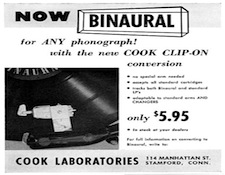

thing, except for Emory Cook’s parallel-groove binaural discs (played with two

spaced phono cartridges on a single tonearm) and a few reel-to-reel stereo tapes,

everything was monophonic (We called it “monaural” then, perhaps to

differentiate it from “binaural”). For another, we, with the certainty of those

who know very little, were sure that the only things that could possibly have

any effect at all on the sound of a HiFi system were the phono cartridge and

the speakers.

We weren’t alone in that belief: With the enamored

gullibility of the 1950s, (It was 1954 when, at the age of twelve, I first

became a “HiFi Crazy”) most people believed

that electronics were “scientific”, and therefore as near to perfect as anyone

could ever want. The magazines of the time (Popular

Electronics and High Fidelity) largely

agreed, and most of the early “authorities”, the most influential of whom was

almost certainly Julian Hirsch, said that it was the electromechanical parts ―

the cartridge and the speakers – that, because of their less-than-perfect

mechanical limitations, were responsible for most of the sonic differences

between one system and another.

Even though we all lusted after a “Mac 30” (or even, please

God, a “Mac 60”, please, please) it seemed perfectly reasonable that the

electronics weren’t going to make any difference to the sound: After all, all

of the electronics of the time claimed THD and IM distortion figures of less

than 1% (certainly, we thought, no one could possibly hear that little

distortion) and all claimed frequency response of 20 to 20,000cps (We didn’t

use “Hertz” [Hz] yet), plus or minus no more than 3dB. That was far better than

the response range of the available records at the time (the typical frequency

response range of even the best tape recorders, microphones, and disc cutting

heads of the day was only claimed to be 50 to 15,000cps +/- 3dB) so we were

perfectly happy with our home-built Heathkit or EICO electronics, and gave no

thought to their sound at all.

As to speakers and cartridges, well, the differences were

OBVIOUS. There was no comparison at all between what we kids – my pals and I –

could afford or scrounge together and, for example, an Electro-Voice Patrician,

a Lansing Hartsfield, or (Wonder and Glory of all wonders and glories) a Bozak

B310, or even between ours and many of the, less expensive but still

unavailable to us, other speakers on the market. Speakers CERTAINLY made a

difference.

Cartridges, too: Until the General Electric “Variable

Reluctance” magnetic cartridges came along, we were all using high output (1

VOLT or more) crystal or ceramic cartridges. Then came the GE cartridge and a

revolution: Its output was so low that I had to spend $13 (big bucks for a

kid!) for a one-tube (12AU7, If I remember correctly) Fisher preamp to boost it

up to where my amp could deal with it. As compared to what I had had before, though,

it was a world of improvement.

The other parts of our systems fell, along with our

electronics, into the “doesn’t affect the sound” category; not because, like

the electronics, they were essentially “perfect”, but because being “part of

the sound” wasn’t their job: The turntable was just something to spin the

records and, as long as it had satisfactorily low wow, flutter, and rumble, it

was just fine. The tonearm was just something to hold the cartridge. And the

wires? They were just wires, and what we all used (and made for ourselves) was

nickel-a-foot Belden microphone cable with two-for-a-nickel cardboard-spaced

“tulip” RCA connectors for hookup, and lampcord for the speaker.

Although we had no way of knowing it, a very major reason

why so much of our system seemed to make so little difference was that we were

listening in mono. With not even any

conception of imaging, soundstaging, or ambience (other than “echo”) those

weren’t things that we listened for, and, when they weren’t there, we didn’t

notice their absence.

When, in 1957, stereo records (and a low-output

Electro-Voice ceramic cartridge to play them) came along, a new door was opened

that, frankly, most of us – even those who had “gone stereo” – didn’t go

through. We were too busy enjoying the glories of Left and Right and spending a

now-utterly-incomprehensible amount of time listening raptly to ping pong games

and marching bands, and grinning like loons as fire engines, jet fighters, and

steam locomotives roared through our rooms at joyously cataclysmic volume.

In fact, though, even if we had known about the real

potential of stereophonic sound, we were probably just too early in the cycle

to actually pass through that “door” and take full advantage of it: Mono didn’t really require “time aligned”

drivers, so most speakers other than those from Tannoy didn’t offer them and

buyers didn’t yet know enough to demand them for their stereo systems. Linn

hadn’t yet demonstrated undeniably that turntables could affect sound quality.

Randall Research and Monster cable hadn’t yet shown those who were willing to

believe their ears that cables CAN be heard and DO affect overall system

performance. With both imaging and soundstaging unknown, no one had even

discovered yet that both imaging and soundstaging could depend on speaker

placement, and “bookshelf” speaker systems were really called that because people

really bought them to be placed on a bookshelf (where, as on a “boombox”, they

would probably be too close together to actually produce a realistic image).

Eventually, though people learned: Speakers got better; “bookshelf” speakers

became “monitors” and were moved off the shelf to stands on the floor, well

away from the walls; better speakers, better turntables, better tonearms,

better cables, and better recording techniques helped people to hear recorded

soundstage and ambience for the first time, and the result was both better

recordings and better electronics.

And at that time, we finally learned what’s important: Everything. It all, every element of the

recording, the system that it’s played on, and even the room that it’s played

in is important. There is no contributing link

anywhere along the chain that doesn’t

affect the sound to at least some degree.

ATTENTION TROLLS: I’m not suggesting that there is no snake oil out there, but we’ve finally gotten to the point where each person, with

his own ears, on his own system, in his own room, can and must decide what works and

what doesn’t, and that’s exactly where we should

be. Good for Us!

My fave quote from the article, “we’ve finally gotten to the point where each person, with his own ears, on his own system, in his own room, can and must decide what works and what doesn’t, and that’s exactly where we should be.”