It’s the time of year for saving money!

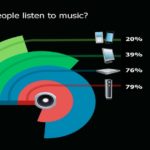

Back when I was a little kid, in the 1940s and early ’50s, my first memories of music were of it played on one-piece systems: a radio, a record player, or even, later on one of the (still very rare, and with a picture that was black-and-white and just a few inches across) television sets. Whichever it was, the thing that I heard the music on was a single box that might have been anything from the size of an ordinary toaster to a major floor-standing piece of furniture, as much as three or four feet tall, that included the sound source — in the case of a radio, an AM (FM didn’t come along until later) tuner; and for a record player, the turntable, arm, and cartridge — plus an amplifier with all of the necessary controls and a speaker (a single “full range” driver, ranging anywhere from about 3 inches in diameter to 12 or even 15 inches, depending on, and proportional to, the size of the box). A television set, even though its screen was tiny by today’s standards, was still usually about as tall as a big “console” radio and also included its own electronics and speaker, and there were also – for the rich or the gadget-crazy –radio/phonograph combinations and even princely units that included a radio, a record player, and a television set, all in one magnificent bakelite, plastic, or hand-rubbed wood cabinet.

Those – all of the things just mentioned – were for the mass market and were hugely successful, but even as early as the 1930s Western Electric and Bell Laboratories (respectively, the manufacturing and research and development arms of the telephone company) and, somewhat later, people like Avery Fisher and H.H. (Herman Hosmer) Scott, were looking at developing music playing devices for the home from a different perspective, entirely.

Those – all of the things just mentioned – were for the mass market and were hugely successful, but even as early as the 1930s Western Electric and Bell Laboratories (respectively, the manufacturing and research and development arms of the telephone company) and, somewhat later, people like Avery Fisher and H.H. (Herman Hosmer) Scott, were looking at developing music playing devices for the home from a different perspective, entirely.

Their goal was music that was more natural-sounding (that, to use the term coined by Avery Fisher, had “high fidelity” to its source), and one of the principles they applied toward achieving it was “perfection through specialization.”

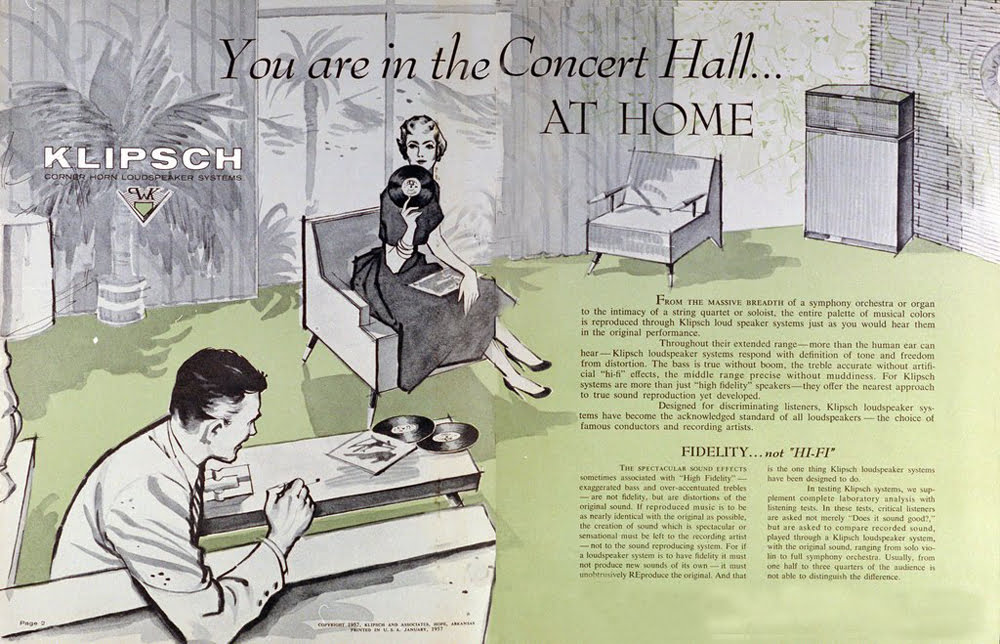

Professional equipment had already specialized, with different companies making different parts of the sound gear for public address (“PA”), recording, and broadcast systems, so it was easy for the new “High Fidelity” sound companies to separate the one-piece systems for home use into a receiver, for all of the source and electronics elements and a separate speaker, mounted separately, set professional-style, in its own “enclosure”. Then, too, because professional users had already discovered that speakers work better if the frequency spectrum is broken-up among a number of drivers instead of trying to reproduce it all with just one, home speaker systems adopted the practice of using a “tweeter” for the highs and a “woofer” for the lows with, sometimes, a “midrange” driver (apparently, no one could come up with a catchy enough nickname) to cover the middle frequencies.

That’s what the first home Hi-Fi systems were: a receiver, a record player or changer, and a separate speaker system. Then, following through on the modular approach being taken with speaker systems, the receiver became what we would call today an “integrated amplifier” plus an (optional) separate tuner – the power supply, control and output sections by themselves, on a single chassis for the amplifier, and the tuner section, now often coupled with an FM tuner (or as just an FM tuner), with its own power supply on a separate chassis.

That’s what the first home Hi-Fi systems were: a receiver, a record player or changer, and a separate speaker system. Then, following through on the modular approach being taken with speaker systems, the receiver became what we would call today an “integrated amplifier” plus an (optional) separate tuner – the power supply, control and output sections by themselves, on a single chassis for the amplifier, and the tuner section, now often coupled with an FM tuner (or as just an FM tuner), with its own power supply on a separate chassis.

When “magnetic”, as opposed to ceramic or “crystal” phono cartridges came along, (the General Electric “variable reluctance” cartridge was the game-changer here) their output was so low by comparison that a “pre-amplifier” device – first available as an outboard unit to be plugged into one of the amplifier’s regular “line level” inputs – was required to make them usable. The improved sound quality from the new cartridges was so great that the extra amplification stage (my first one was a one-tube “outboard” device from Fisher Radio that used a 12AX7 and cost $13.00) was quickly accepted as a necessity and everybody started either building one into their receivers or integrated amplifiers or, offering two new kinds of products for home use: A separate “control-preamplifier” (which offered a volume control, tone and “loudness” controls, and phono preamplification to, before the industry standardized on the RIAA curve, correct for as many as a dozen selectable phono equalization curves), and a no controls at all, “basic” power amplifier.

By that point, “component” Hi-Fi was, including the outboard DACs (digital-to-analog converters) and other free-standing source devices and pre-preamplifiers or input transformers (for phono cartridges with really low-output), fully complete, and you could buy just about anything you wanted as a specialized (and hopefully better-because-of-it), single-purpose product.

And then do you know what happened?

Some manufacturers went even further, and started making products that were even more modular – like a number of preamp builders who, claiming performance advantages, put their preamps and associated power supplies on separate chassis, and other companies, like DCS for example, who went even beyond that, to produce a three chassis CD player (and I’ve heard rumors that there may be one out there with as many as four separate functional chassis).

Still other companies, though, started a movement in the opposite direction – even at the very High End, where Krell, as just one example, is now offering, in addition to its separate component line, an integrated amplifier, fully fitted-out with all of the very latest toys and goodies.

Things are starting to come back together again, and I personally think that that can be a good thing: For one thing, sharing power supplies for multiple functions can – assuming that we’re talking about good and suitable power supplies – save space, complexity, and expense to the user. Combining functions also makes for fewer components in a system, which saves on “sheet metal” costs; makes for simpler hookup and reduced likelihood of component-to-component incompatibilities; and also reduces the possibility of “ground loops” and other sonic horrors. Importantly, fewer things to hook together also means that fewer cables will be required to make the necessary connections, and that, just in itself, can represent both a noticeable sonic improvement and – given the prices that some of the current cable lines have achieved since I left the market — a considerable financial saving.

Things are starting to come back together again, and I personally think that that can be a good thing: For one thing, sharing power supplies for multiple functions can – assuming that we’re talking about good and suitable power supplies – save space, complexity, and expense to the user. Combining functions also makes for fewer components in a system, which saves on “sheet metal” costs; makes for simpler hookup and reduced likelihood of component-to-component incompatibilities; and also reduces the possibility of “ground loops” and other sonic horrors. Importantly, fewer things to hook together also means that fewer cables will be required to make the necessary connections, and that, just in itself, can represent both a noticeable sonic improvement and – given the prices that some of the current cable lines have achieved since I left the market — a considerable financial saving.

We’re also seeing more and more “wireless” speakers, even from great companies like Dynaudio. These avoid the need for speaker cables by combining the power amplifier and the speaker elements in the same box – just as they were in the “consoles” and other one-piece units of yore — and hooking them together with their control units by a radio link. As to whether the radio link is better from a performance standpoint than a well-designed cable may be debatable, but it certainly does provide welcome convenience for its user and a new selling point for the manufacturer.

All in all, it looks like the wheel may be making another turn, back to the more fully integrated unit systems that Hi-Fi started with. Or it might just be adding new products for more convenience, better value, possibly better performance, and more available choice.

All in all, it looks like the wheel may be making another turn, back to the more fully integrated unit systems that Hi-Fi started with. Or it might just be adding new products for more convenience, better value, possibly better performance, and more available choice.

Whatever it is, I think it’s a good thing for all of us and I’ll be following it closely!