It’s the time of year for saving money!

Talking with an audio manufacturer the other day, I was struck with a realization: This whole DAC thing has gotten ridiculous. Well, not the whole DAC thing. Just the part about format compatibility.

These days, many audiophiles choose their DACs like people used to choose their stereo receivers in the 1970s: by the numbers. The more formats the DAC will accept, and the higher the resolutions it will accept, the better. Any DAC that doesn’t have all the checkboxes filled in falls out of consideration.

These days, many audiophiles choose their DACs like people used to choose their stereo receivers in the 1970s: by the numbers. The more formats the DAC will accept, and the higher the resolutions it will accept, the better. Any DAC that doesn’t have all the checkboxes filled in falls out of consideration.

“At this point, every DAC needs to have DSD,” I heard one audiophile tell another at RMAF — and that was two years ago, when DSD was just starting its purported resurgence. (Which may be a poor choice of wording on my part because it implies that at some point in the past, DSD had once surged.) I’ve heard several manufacturers fret when a DAC or digital preamp was too far along in its development to change, but it didn’t have the very latest and supposedly greatest digital technology.

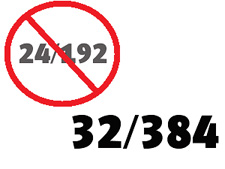

Let’s consider what benefits ultra-high-resolution audio brings. At a sampling rate of 96 kilohertz, with a practical bandwidth of about 40 kHz, you’re already at double the best-case bandwidth of the human ear — and triple the bandwidth of the typical middle-aged male human ear. Step up to 192 kHz sampling, and you can double all those numbers.

Now there are DACs that can handle signals with sampling rates up to 384 kHz, in which case you can double those numbers again. So you’re at eight times the bandwidth a young child can hear, and 12 times the bandwidth you can likely hear.

Some audio enthusiasts cite the ability of the human ear to perceive timing differences of as little as 10 microseconds (the duration of a single cycle at 100 kHz) as evidence that we can hear the advantages of ultra-high digital audio sampling rates. However, I know of just one study that supports the idea that we can detect anything at all above 20 kHz, and it concluded, “While we observed audible differences between sample rates of 88.2 and 44.1 kHz, they remain very subtle and difficult to detect.” Thus, it seems extremely unlkely that any study could find a significant benefit in going from 88.2 or 96 kHz to rates above 192 kHz.

There’s been talk of distributing music at 32-bit resolution, and there are already DACs that can accept these files. With 24-bit digital files, you’re getting a theoretical dynamic range of 144 dB. Stepping up to 32 bits would give you a theoretical 192 dB dynamic range. The word “theoretical” is vital to this discussion, because the range from the noise floor of a very good home listening room to the loudest sound you’d want to expose yourself to is about 80 dB. In a professional recording studio, it might be 90 dB. Even though you can hear sounds below the noise floor, 24 bits is more than enough to capture them all. One of my colleagues during my time at Dolby Labs once joked that in order to exploit the full dynamic range of 24-bit audio, you’d have to freeze your microphones in nitrogen. Stepping up to 32-bit resolution makes sense in digital audio processing, but there’s absolutely no reason to use it for music distribution.

And then we get into DSD. We’re now seeing DSD downloads being offered at a sampling rate of 5.6 MHz, double the typical rate of 2.8 MHz. DSD is already a niche within the high-res audio niche, and to my knowledge it has never demonstrated a superiority to standard PCM recording. Yet now electronics manufacturers will be expected to support this new double-rate version of DSD, and probably quad-rate and octuple-rate versions of DSD in the future — even though it’s unlikely that the person who buys these DACs will actually own more than handful of such ultra-high-resolution files.

Digital audio is getting to be too much like TVs. The TV industry has embraced 4K technology as the next great thing, even though its increased resolution can be appreciated at normal viewing distances only on screens measuring about 80 inches and larger. Despite its negligible benefit, we’re already seeing video distributed in (and Internet bandwidth wasted on) 4K.

And now the TV industry has started to talk about 8K. Why? Because it’s a bigger number than 4K, so at least some people will buy it even if it has zero benefit.

I hope the audio industry doesn’t follow this path, wasting its efforts on increasingly imperceptible “improvements” in digital audio resolution when it could be pursuing real improvements.

The camera industry got it right. Buying a digital camera used to be all about “How many megapixels does it have?” But once we got to the point where 16-MP cameras were commonplace, resolution became a given. Consumers realized that every good camera had way more resolution than they could use, and they by and large quit worrying about the megapixels and started focusing on things that could make a real difference: better lenses, better autofocusing, more flexible video capabilities, improved low-light performance, etc.

Personally, I don’t give a damn about double-rate DSD or 32/384 PCM. Audio writers often repeat the shibboleth that “more resolution is always better,” but at this point, when the capabilities of our digital technologies so greatly exceed the capabilities of our ears, this statement is simply false. And it’s downright harmful when it shifts the industry’s product development resources away from technologies that might deliver a real benefit.

Like a set of headphones that cancels noise as well as the Bose QC25 but sounds as good as the Audeze LCD-X. Or a Bluetooth speaker that really, truly sounds like a small stereo system. Or a small subwoofer with the output and the sound quality of the big models from Hsu, Power Sound Audio and SVS.

Got any more good ideas for the audio industry? Let’s hear ’em …