It’s the time of year for saving money!

Quite frankly, I like speakers a whole lot more than headphones. I’ve tried the latest and greatest of every style of ‘phone at Shows and I own three sets of Stax electrostatics (Lambda Pro, Sigma, and SR-80 Pro) and both of the top-of-the line earbud models (3 driver and the yummy new 4 driver) from 1More, and for me, despite how great the headphones’ sound may be, for most background or other uncommitted listening, speakers still offer a number of advantages that I find important: For one thing, I’m not on a leash when I listen to them. (Even with 15 foot extension cords, I still feel spatially constrained.) For another, I don’t like the fact that, when I’m wearing headphones of any kind, if I move my head, the whole orchestra moves with me. (That seems always to happen just as I’m settling-in to really enjoy the music, and it always reminds that I’m listening to a recording, and not the real thing) Finally, at least in stereo, although I’ve been told that there’s software available that can make it otherwise, I don’t like the way headphones (even my Stax Sigmas and the AKG K1000s, which were specifically designed to counter it) image inside my head, instead of in front of me, as speakers do.

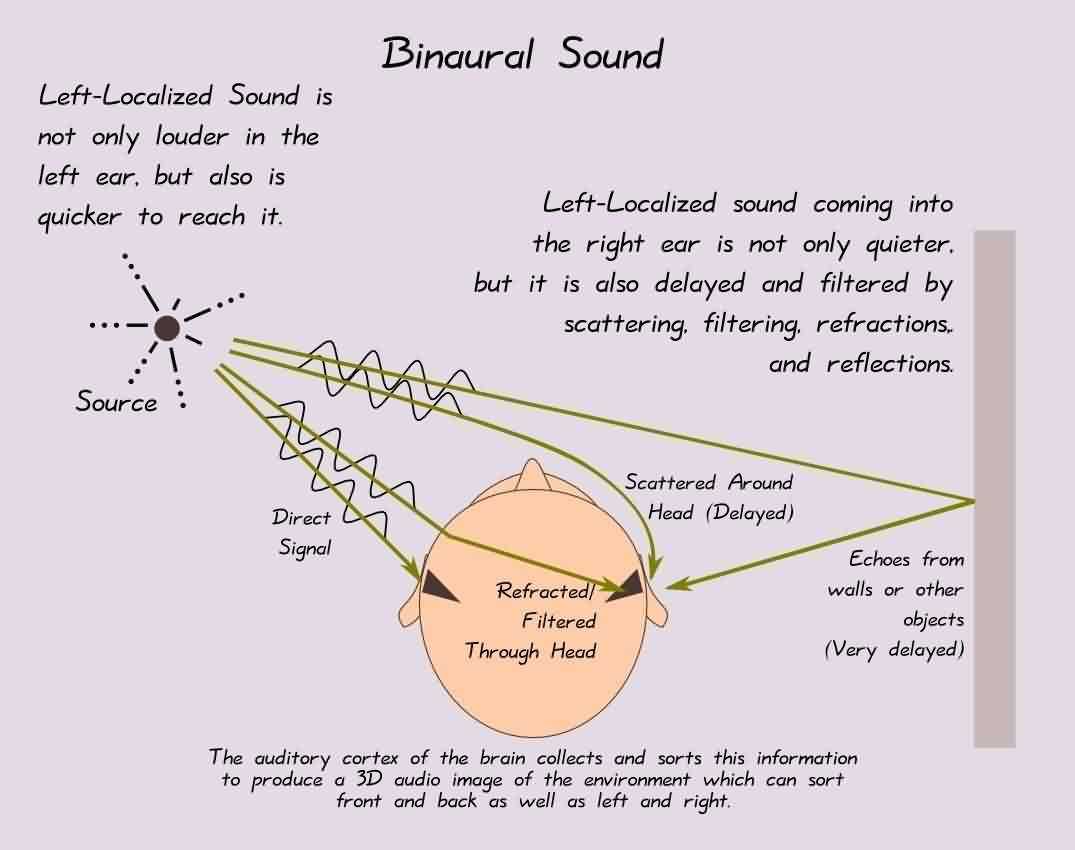

In terms of a pleasant background or even serious listening experience, speakers, IMHO, are the champs. For sheer reality, though – for the seemingly palpable duplication of a real musical or sonic experience – headphones, providing that they’re playing a binaural source, have no equal.

In terms of a pleasant background or even serious listening experience, speakers, IMHO, are the champs. For sheer reality, though – for the seemingly palpable duplication of a real musical or sonic experience – headphones, providing that they’re playing a binaural source, have no equal.

It’s not just that binaural is all that good; it’s that stereo has problems that binaural will.

The original stereo recordings, as I’ve mentioned earlier, were done very simply, usually with an “A-B” mic array (two mics, usually “omnis”, spaced from a couple of feet to about eight feet apart). That kind of recording, where the mics are spaced differently than your ears and the playback is through speakers, also spaced differently than your ears (and probably even differently than the microphones) creates, as I described in earlier parts of this series, problems of arrival time and phase that make it impossible for stereo to truly duplicate the original experience.

Another problem that stereo has is that differing distances from the microphones to the artists and instruments in a large group – a symphony orchestra, for example, perhaps with a solo vocalist (the fat lady in the Viking helmet and armor, if it’s an operatic recording) – can result in significant differences in relative level (how loud everything is) that can result in some performers appearing more or less prominent in the recording than they actually were in the actual performance. To counter that, a number of things have been tried: One is just to rearrange the group so the “balance” will be better. That may sound more accurate, but, for stereo, it necessarily presents a different-from-normal “image”. Another thing that has been done quite commonly is to use “spot” mics on individual performers, to set them more properly in perspective or to bring a player far back in the orchestra up to “center stage, front” for a solo and then move him/her back into the group by just changing that mic’s volume on a mixing board. Sometimes this has gotten out of hand, and we’ve all seen pictures of recording sessions where there seemed to be one mic per performer or as many as five mics on just a single drum set.

By the 1950s, and ’60s, this practice finally got so complicated and so difficult to edit or mix that multi-track recording was developed to improve, and ultimately replace it. That, as originally just 3 channels, allowed recording engineers to record (for example) the orchestra on two stereo channels and a singer on a third “center” channel, so that orchestral/vocal relative volume or tonal balance could be changed or adjusted or the tracks individually edited even after the recording was long finished. That being the case, it didn’t take engineers long to figure out that the singer didn’t even need to be present for the orchestral recording session, but could be added later. And once that happened, the recording art changed, entirely. The number of available channels on studio tape recorders exploded, eventually getting as high as 48 or even 64 tracks (using two linked 24 or 32 track machines), and – except for much of recorded classical music ― it became a common practice to record singers and orchestra, or individual sections (rhythm, strings, brass, etc.), or even individual instruments on separate tracks at different times; possibly even in different acoustical environments; and to edit, equalize, and add “effects” to each of the tracks separately.

By the 1950s, and ’60s, this practice finally got so complicated and so difficult to edit or mix that multi-track recording was developed to improve, and ultimately replace it. That, as originally just 3 channels, allowed recording engineers to record (for example) the orchestra on two stereo channels and a singer on a third “center” channel, so that orchestral/vocal relative volume or tonal balance could be changed or adjusted or the tracks individually edited even after the recording was long finished. That being the case, it didn’t take engineers long to figure out that the singer didn’t even need to be present for the orchestral recording session, but could be added later. And once that happened, the recording art changed, entirely. The number of available channels on studio tape recorders exploded, eventually getting as high as 48 or even 64 tracks (using two linked 24 or 32 track machines), and – except for much of recorded classical music ― it became a common practice to record singers and orchestra, or individual sections (rhythm, strings, brass, etc.), or even individual instruments on separate tracks at different times; possibly even in different acoustical environments; and to edit, equalize, and add “effects” to each of the tracks separately.

Thus arose our current concept of “mastering”, and it and the people who do it became a critical part of modern recording. There’s no denying that modern studio recording can be spectacular and wonderfully enjoyable, or even that, with augmentations like “Q-sound” or other processes, it can offer wonderful spatial presentation. It can be truly amazing… but it can’t be real.

Even without multi-track recording, multi-mic recording takes all of the problems of two-channel, two-microphone recording and makes them worse: Not only do you get all of the problems of timing and phase produced by two microphones hearing all of the music (right left, left, and center) from two different positions, both different from the positions of a pair of human ears hearing the same thing; you also get the timing delays and phase problems of all of the other microphones at all of their other spacings added-in, along with some possible phase cancellations and phase artifacts created as heterodynes (“beat frequencies” as the sound from all of the different microphones hearing the same thing, but in different phase and at different times gets mixed into the same recording channel. When you then add-in multiple tracks, too, each possibly having multiple microphones and (possibly) with not all tracks being recorded in the same acoustical environment (even an “isolation booth” for a soloist might qualify as that) things get mightily screwed-up and we can readily understand the origin of the term “fix it in the mix”.

Even without multi-track recording, multi-mic recording takes all of the problems of two-channel, two-microphone recording and makes them worse: Not only do you get all of the problems of timing and phase produced by two microphones hearing all of the music (right left, left, and center) from two different positions, both different from the positions of a pair of human ears hearing the same thing; you also get the timing delays and phase problems of all of the other microphones at all of their other spacings added-in, along with some possible phase cancellations and phase artifacts created as heterodynes (“beat frequencies” as the sound from all of the different microphones hearing the same thing, but in different phase and at different times gets mixed into the same recording channel. When you then add-in multiple tracks, too, each possibly having multiple microphones and (possibly) with not all tracks being recorded in the same acoustical environment (even an “isolation booth” for a soloist might qualify as that) things get mightily screwed-up and we can readily understand the origin of the term “fix it in the mix”.

It’s stereo’s problems of timing and phase differences, both in recording and playback, that have caused the need for multi-mic’ing and all the rest, and each of those improvements has created its own new problems while trying to solve the others already there.

Binaural recording and playback through headphones proves that the Purists in audio have been correct all along: With only one microphone and one playback transducer system (I say “system” in reference to my 1More [brand] earbuds – and possible others like them – that have three or four transducers for each ear), each placed, as nearly as possible, to duplicate the positioning of human ears, we hear sound exactly as if we were at the session, and both the need for and the possibility of, multiple microphones, multiple tracks, and most of the other studio “tricks” are eliminated, leaving only the reality of the musical or other sonic experience.

Some good things that only stereo can do (multi-time, multi environment recording and the finer arts of editing and mastering) are necessarily lost, but what’s left is enough to keep me listening to binaural whenever I can, even despite my other feelings about headphones.

If you haven’t heard good binaural sound yet, I urge you to do so: You’ll be hooked for life. And to you record producers and recording engineers out there; give us more binaural recordings. If you’ve got em, we’ll buy ’em!