It’s the time of year for saving money!

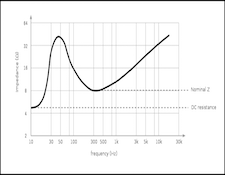

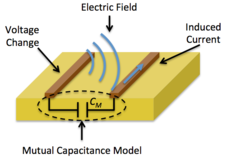

Back before I sold that company in 2002, XLO would occasionally get a phone call or e-mail from a customer or potential customer asking what the capacitance-per-foot of one of our cables was. For some reason, it was always capacitance [C] that they inquired about, even though most people — even “cable doubters”; people who will tell you that cables don’t materially affect the sound of your system — know that resistance [R], inductance [L], and sometimes characteristic impedance [Z0] (which is calculated from the others) are also significant considerations in cable performance.

Certainly there are reasonable reasons for wanting to know a cable’s capacitance: One might, as just mentioned, want to calculate its characteristic impedance, for example, but for most cables to be used in or near the audio frequency range (nominally 20-20,000 Hz), unless they are to be used in a balanced or differential circuit or are going to be extremely long, their characteristic impedance is utterly irrelevant. And, besides that, if the inquirer wanted to know the cable’s characteristic impedance, why not simply ask for it, instead of asking for just one of the numbers necessary to calculate it?

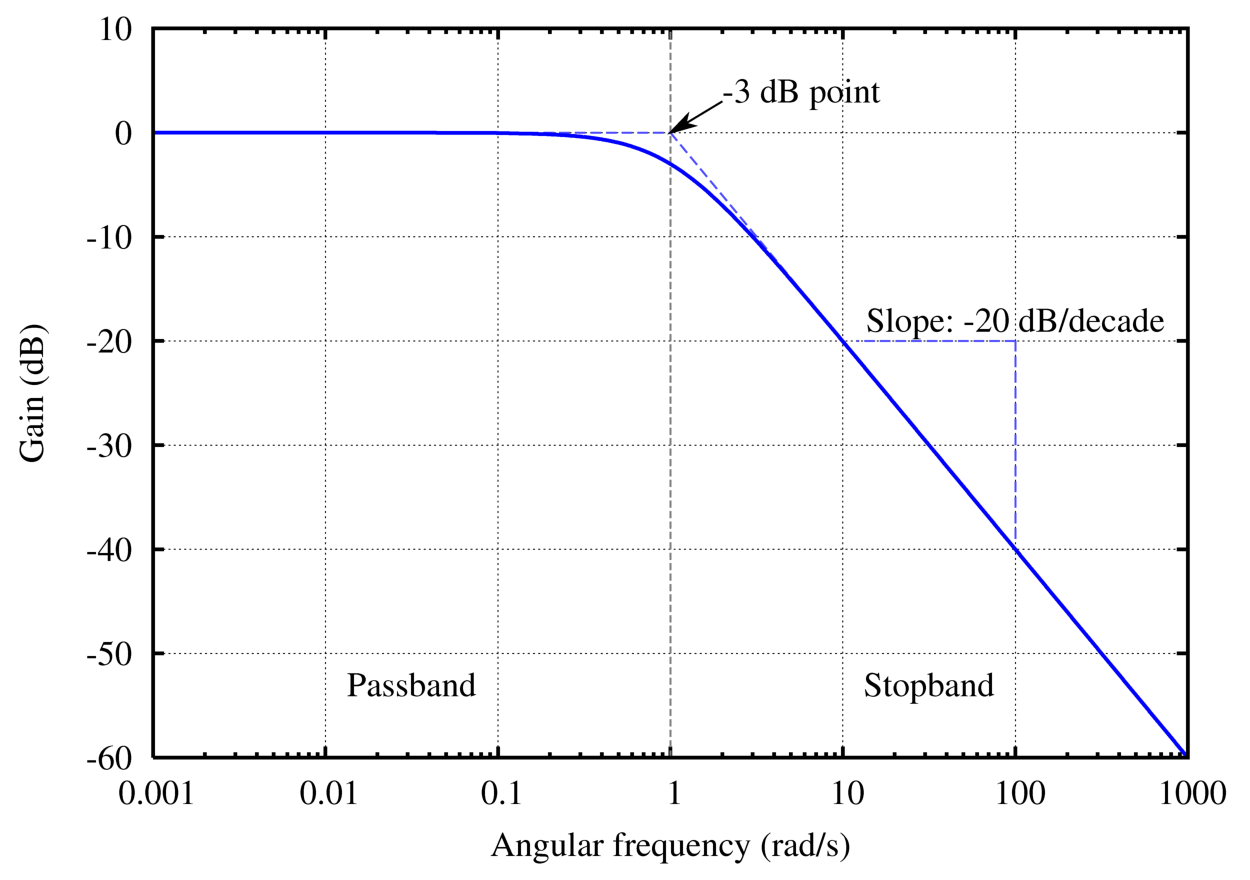

It’s also possible that they were concerned about filter effects (a single capacitor in series can act as a “high-pass” filter) but the amount of capacitance available in the overwhelming number of cables of anything like ordinary length would have little, if any, usable effect in the audio range.

The fact of it was, very simply, that most people who inquired had no good reason to, but were simply asking because they had heard or read somewhere that low capacitance was a good thing for a cable to have. It’s the same, of course, with resistance and inductance – with long enough lengths of cable, they can have significant and clearly audible effects, but not at the lengths we normally use. And, if we want to lower the values of R and L in our system, all that’s necessary to do may be to use shorter cables.

There are other specifications that we, as audiophiles (my friends and I prefer to think of ourselves as “Hi-Fi Crazies”) have relied on over time in trying to evaluate products that have been offered to us: Probably the most commonly looked-to of these is “frequency response”, and that’s been a source of confusion for as long as our hobby has existed.

I mentioned just a few paragraphs back, that the audio frequency range is currently considered to be (nominally) 20 to 20,000Hz. (Back in the 1950s, they used a different number, most commonly 50-15,000 Hz , that was more compatible with the capabilities of the recording and playback equipment available at the time.) Whichever number you might use, it’s utterly meaningless all by itself: For example, how often have you seen an ad for some piece of gear or pre-packaged system that claimed a frequency response of 20 -20,000 Hz, but didn’t say plus or minus what; or measured how? The fact of it is that, in many cases, even the junkiest electronics or the cheapest or tiniest speaker will put out some measurable level of output at either of the stated frequency extremes (20Hz or 20kHz), and the manufacturers or marketers of it can therefore make their claim without actually lying. The truth though may be that, while the range claimed is really there, the level of output at its extremes may be so vastly far below the level available at 1kHz (a commonly used standard measuring point), as to be utterly inaudible, even with your ear touching the speaker.

I mentioned just a few paragraphs back, that the audio frequency range is currently considered to be (nominally) 20 to 20,000Hz. (Back in the 1950s, they used a different number, most commonly 50-15,000 Hz , that was more compatible with the capabilities of the recording and playback equipment available at the time.) Whichever number you might use, it’s utterly meaningless all by itself: For example, how often have you seen an ad for some piece of gear or pre-packaged system that claimed a frequency response of 20 -20,000 Hz, but didn’t say plus or minus what; or measured how? The fact of it is that, in many cases, even the junkiest electronics or the cheapest or tiniest speaker will put out some measurable level of output at either of the stated frequency extremes (20Hz or 20kHz), and the manufacturers or marketers of it can therefore make their claim without actually lying. The truth though may be that, while the range claimed is really there, the level of output at its extremes may be so vastly far below the level available at 1kHz (a commonly used standard measuring point), as to be utterly inaudible, even with your ear touching the speaker.

To give a better idea of their products’ performance, most reputable manufacturers will state (or graphically indicate) a “base” output at some level of signal input and state the frequency response of their products as being within some range of that level. The most common of such ranges for speakers (but used for other things, as well) is “plus or minus 3 decibels, normally written as “+/- 3dB”. Because output levels function logarithmically, with + 3dB indicating a doubling of the output from its prior level and -3dB indicating a halving of it, even that’s not really much of an indicator of what something will actually sound like: Although the actual figure will vary from person-to-person and test results have varied widely, a difference of 3dB in frequency response, one way or another, may be not much louder or quieter than the smallest level of difference a person can easily notice.

Compounding the problem is the fact that even that “+/- 3dB” description can be so broad as to be near-meaningless. For example, if, across a broad range of frequencies, one frequency is 3dB, but no more than that, below the base level (the “flat” line) and one is 3dB, but no more than that above it, it will certainly qualify as having a frequency-response within the stated range. But so will a product with nothing below the line and one or more +6dB peaks. Or one that alternates by 3dB above and 3dB below base level every half octave. All of them will strictly adhere to the claimed performance specification, but all will be (and probably sound) completely different.

Compounding the problem is the fact that even that “+/- 3dB” description can be so broad as to be near-meaningless. For example, if, across a broad range of frequencies, one frequency is 3dB, but no more than that, below the base level (the “flat” line) and one is 3dB, but no more than that above it, it will certainly qualify as having a frequency-response within the stated range. But so will a product with nothing below the line and one or more +6dB peaks. Or one that alternates by 3dB above and 3dB below base level every half octave. All of them will strictly adhere to the claimed performance specification, but all will be (and probably sound) completely different.

Output level specs for power amplifiers are another thing that is often stated, but doesn’t really tell much: If , for example, an amp is rated at 100 Watts “peak” power, what does that mean? What about IHFM (Institute of High Fidelity Manufacturers) “music power”? Or RMS? The fact of it is that “100 Watts” can mean a broad range of real power levels, depending on how it’s tested and stated, and, because our hearing is logarithmic in function, the apparent loudness difference between an amplifier of (however it’s stated) 10 Watts and 100 Watts (or 100 Watts and 1,000 Watts) will only be 10 decibels – certainly a clearly noticeable difference in overall volume, but no more than the typical amount of boost or cut provided by a tone control at a specific frequency above or below its turnover frequency and the general level.

On top of that, there’s distortion. When I was a kid, Hi-Fi gear routinely quoted specs for Total Harmonic Distortion (“THD”) and for Intermodulation Distortion (“IM”). Later, there was Transient Intermodulation Distortion (“TIM), and, in recent years, we seem to have come around to the point where THD is the only distortion spec commonly given. What does this all mean? IMHO, not very much. Back in the 1970s and’80s, the large, principally Japanese “Mid-Fi” manufacturers discovered or fell in love with global feedback and applied it to produce amplifiers with claimed distortion of as little as 0.0001% (one ten thousandth of one percent)THD. The result? Amplifiers that had specifications better than had ever been seen before, but that were often less good-sounding than the products they replaced.

On top of that, there’s distortion. When I was a kid, Hi-Fi gear routinely quoted specs for Total Harmonic Distortion (“THD”) and for Intermodulation Distortion (“IM”). Later, there was Transient Intermodulation Distortion (“TIM), and, in recent years, we seem to have come around to the point where THD is the only distortion spec commonly given. What does this all mean? IMHO, not very much. Back in the 1970s and’80s, the large, principally Japanese “Mid-Fi” manufacturers discovered or fell in love with global feedback and applied it to produce amplifiers with claimed distortion of as little as 0.0001% (one ten thousandth of one percent)THD. The result? Amplifiers that had specifications better than had ever been seen before, but that were often less good-sounding than the products they replaced.

It’s often that way with specifications: Many give a misleading picture and, as a result, many reputable audio manufacturers – especially at the very High-End – either no longer publish them or have reduced those that they do release to the barest minimum.

Good.

Use your ears. They’re the best test instrument the world has ever known. Your system is for your own enjoyment; why look to others for information about how good it is when you can simply hear it for yourself?