It’s the time of year for saving money!

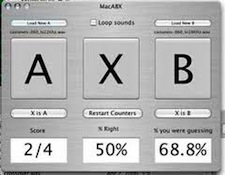

By now, you probably know what a “double blind” test is: Instead of a “single-blind” test like the famous “Pepsi Challenge”, where a tester, who knows which sample is which, asks a person who doesn’t, which of two soda pops he likes better, in a double-blind test, neither the tester nor the “testee” has any clue as to which glass holds the Pepsi.

The claimed benefit of doing it that way is greater objectivity: If the tester doesn’t know what’s in which glass he can’t, either purposely or through body language or some other way, bias the test.

The claimed benefit of doing it that way is greater objectivity: If the tester doesn’t know what’s in which glass he can’t, either purposely or through body language or some other way, bias the test.

Sometimes it even works, and in many fields of science, where one single factor can be effectively identified and isolated, double-blind testing is the preferred method and really can make for more reliable data. In audio, though, except under very special circumstances, that’s simply not the case.

Unlike a whole lot of other hobbies and pastimes, audio is either plagued by or — if you like that sort of thing – blessed with constant dispute. In baseball, although the umpire can be wrong about some things, you can always tell for certain if the batter actually hits the ball and if the fielder actually catches it. Those are indisputable, as is the measured speed and quarter-mile-elapsed-time of a dragster. And, in the case of a “photo finish”, whether of cars or horses or anything else, you can accurately record and measure the results and you can ALWAYS rely on what the measurements say. The same is true for photography, another favorite hobby of many audiophiles; where nobody would ever even consider arguing that different lenses, different film, or a different pixel count (for digital photography) don’t make a difference, but in audio, argument about the basics has been going on ever since the hobby started, and there’s no sign that it’s ever going to stop.

The reason for this ISN’T that Hi-Fi Crazies are inherently irrational or that their perceptive senses are either flawed or easily fooled; it’s that, unlike all of those other fields, disciplines, or pastimes, in audio it’s almost impossible to isolate any one single criterion to test, and even if that could be done, it would still be almost impossible to get any two or more people to opine on only just that one thing, and even if that COULD happen, the odds are that their opinions would have little value.

The reason for this ISN’T that Hi-Fi Crazies are inherently irrational or that their perceptive senses are either flawed or easily fooled; it’s that, unlike all of those other fields, disciplines, or pastimes, in audio it’s almost impossible to isolate any one single criterion to test, and even if that could be done, it would still be almost impossible to get any two or more people to opine on only just that one thing, and even if that COULD happen, the odds are that their opinions would have little value.

To show you what I mean, let’s first take a look at a double-blind audio test that might actually work: (Remember that I DID say that “under very special circumstances” that could happen.) For our test material, let’s play a 2 kHz sine wave in 20 second samples, repeating the samples at two different volume levels precisely 2dB apart. If all of our testees listen to the same sample at the same time, through identical headphones, and if the sample volume levels are selected by a computer controlled by a random numbers generator, and if we record them for proof of sequence, but tell neither the subjects nor the researchers which volume level is actually playing at any given time, we will have what ought to satisfy even the most rigorous researcher as being a genuine double-blind test.

If the purpose of our testing is to determine whether people can identify 2dB differences in volume, and if each time a sample is played the testees are asked to state whether it is of the greater or lesser volume level, what they tell us they hear, compared to what was actually presented should be sufficient to allow us to reach some reasonably “high confidence” conclusions, and the reason for that will be that we will have isolated one single changing factor – the volume level — and held every other element of the test absolutely constant: All of the testees will have listened to exactly the same test material at exactly the same time, through exactly the same sound sources, spaced exactly the same distance from their ears in exactly the same (because the headphones will effectively eliminate any room acoustics) acoustical environment, and, other than the relative volume levels, there will have been no variable factors at all.

If the purpose of our testing is to determine whether people can identify 2dB differences in volume, and if each time a sample is played the testees are asked to state whether it is of the greater or lesser volume level, what they tell us they hear, compared to what was actually presented should be sufficient to allow us to reach some reasonably “high confidence” conclusions, and the reason for that will be that we will have isolated one single changing factor – the volume level — and held every other element of the test absolutely constant: All of the testees will have listened to exactly the same test material at exactly the same time, through exactly the same sound sources, spaced exactly the same distance from their ears in exactly the same (because the headphones will effectively eliminate any room acoustics) acoustical environment, and, other than the relative volume levels, there will have been no variable factors at all.

]]> What, though, if we were to change just one thing? What if, instead of individual headphones for each testee, we were to use a single loudspeaker to provide the sound for the entire group?

Immediately there would be problems: Not all of the listeners would be at precisely the same distance from, or at the same angle to the face of the speaker; the speaker’s dispersion pattern at 2 kHz, coupled with room reflections, refraction, and absorption, might mean that no two testees would actually be presented with exactly the same sound to listen to, and the whole test might start to fall apart.

If, instead of just a single speaker, we were to use two – a stereo pair – the problem might be made even worse, and the whole test could very well become unworkable, even with just a simple sine wave as the test material.

If, as is ALWAYS the case when comparisons are made of audio gear, we were to use music instead of a single tone as the test material, our chance of actually drawing any kind of reliable conclusion would become almost nil: If we were to use speakers and do a group test, the problem would again arise that no two people can ever be in exactly the same physical relationship to the sound sources, and speaker dispersion patterns and room acoustics would make it impossible for any two people to hear exactly the same thing. And if the music were in stereo, the problem would be compounded by the fact that listeners to the left of center would hear instruments to the right of center differently than would listeners to the right of center – and vice versa.

Going to headphones instead of speakers could solve that one kind of problem, but another kind of problem would still remain – one that is simply a fact of human nature, and that can never be successfully overcome: Whereas the single tone of the initial test has only two real characteristics – frequency and amplitude, and both the frequency and the amplitude are held constant, making them easy to isolate and concentrate on, music is made up of multiple tones at multiple amplitudes, interspersed with varying intervals of (more or less) silence, all constantly changing. This means that in addition to just frequency and amplitude, music has dynamics, transient attack and decay, sum and difference (heterodyne) frequencies created by the other (“real”) frequencies, and any number of other characteristics — a whole “alphabet” of characteristics for the testees to listen to – and, human beings being what they are, each will hear that alphabet in a different way, giving greater notice or attention to some characteristics and less or none at all to others.

Not only that, but not all samples of music will contain all of the “letters” of the “alphabet”, and a piece of gear that does particularly well or particularly poorly with some particular “letter” may not have its abilities exposed to the testees if that letter is not present in the sample. Furthermore, in order to get in as many “letters” as possible, the test must necessarily be of longer duration per sample than a test involving just a single tone, and that can mean problems, just in itself, because of the nature and duration of most people’s auditory memory.

What, though, if we were to change just one thing? What if, instead of individual headphones for each testee, we were to use a single loudspeaker to provide the sound for the entire group?

Immediately there would be problems: Not all of the listeners would be at precisely the same distance from, or at the same angle to the face of the speaker; the speaker’s dispersion pattern at 2 kHz, coupled with room reflections, refraction, and absorption, might mean that no two testees would actually be presented with exactly the same sound to listen to, and the whole test might start to fall apart.

If, instead of just a single speaker, we were to use two – a stereo pair – the problem might be made even worse, and the whole test could very well become unworkable, even with just a simple sine wave as the test material.

If, as is ALWAYS the case when comparisons are made of audio gear, we were to use music instead of a single tone as the test material, our chance of actually drawing any kind of reliable conclusion would become almost nil: If we were to use speakers and do a group test, the problem would again arise that no two people can ever be in exactly the same physical relationship to the sound sources, and speaker dispersion patterns and room acoustics would make it impossible for any two people to hear exactly the same thing. And if the music were in stereo, the problem would be compounded by the fact that listeners to the left of center would hear instruments to the right of center differently than would listeners to the right of center – and vice versa.

Going to headphones instead of speakers could solve that one kind of problem, but another kind of problem would still remain – one that is simply a fact of human nature, and that can never be successfully overcome: Whereas the single tone of the initial test has only two real characteristics – frequency and amplitude, and both the frequency and the amplitude are held constant, making them easy to isolate and concentrate on, music is made up of multiple tones at multiple amplitudes, interspersed with varying intervals of (more or less) silence, all constantly changing. This means that in addition to just frequency and amplitude, music has dynamics, transient attack and decay, sum and difference (heterodyne) frequencies created by the other (“real”) frequencies, and any number of other characteristics — a whole “alphabet” of characteristics for the testees to listen to – and, human beings being what they are, each will hear that alphabet in a different way, giving greater notice or attention to some characteristics and less or none at all to others.

Not only that, but not all samples of music will contain all of the “letters” of the “alphabet”, and a piece of gear that does particularly well or particularly poorly with some particular “letter” may not have its abilities exposed to the testees if that letter is not present in the sample. Furthermore, in order to get in as many “letters” as possible, the test must necessarily be of longer duration per sample than a test involving just a single tone, and that can mean problems, just in itself, because of the nature and duration of most people’s auditory memory.

In short, for the important stuff, like “Do amplifiers or cables or differing storage media sound different”, “blind testing” of any kind, single or double isn’t likely to work because there are simply too many characteristics present and changing, and (if only because of the way human perception works) it’s virtually impossible to isolate them and make sure that all of the testees are hearing the same test of the same thing in exactly the same way.

And for the other stuff, the things like simple comparisons of single frequency relative amplitude? Well, yeah, it may be possible to do a valid blind test of them, but so what, and who cares? For information like that, it’s both easier and more accurate to just hook them to a meter and get whatever information you might want directly! Why bother with any other kind of testing at all?

In short, for the important stuff, like “Do amplifiers or cables or differing storage media sound different”, “blind testing” of any kind, single or double isn’t likely to work because there are simply too many characteristics present and changing, and (if only because of the way human perception works) it’s virtually impossible to isolate them and make sure that all of the testees are hearing the same test of the same thing in exactly the same way.

And for the other stuff, the things like simple comparisons of single frequency relative amplitude? Well, yeah, it may be possible to do a valid blind test of them, but so what, and who cares? For information like that, it’s both easier and more accurate to just hook them to a meter and get whatever information you might want directly! Why bother with any other kind of testing at all?

Ridiculous double talk. One person, one room. Keep everything the same and swap out a single component. I particularly want to watch with the thousand dollar iec power cables.

Short term double blind has never worked, not to mention, it’s useless. People ultimately buy what they like and can afford. The people doing the arguing aren’t the ones spending the money.

I think you’re overcomplicating the problem. If you’re comparing amplifiers, check the frequency response curves to ensure they are comparable, have them both set to the same volume level within .2 dB and let the subject choose music that he is familiar with and switch between the two. Which one sounded better? Note the results, randomize the amps, and test again. Rinse and repeat. See if a preference emerges for a particular amp. Bring in more test subjects and see if there is a consensus.