It’s the time of year for saving money!

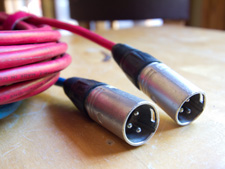

Last week, while I was running frequency response measurements on a couple of soundbars, it dawned on me that the blue cable I was using to connect my test microphone is one the oldest pieces of audio/video gear I own, the other being its red twin. I’ve owned the pair since 1992. They’ve been hauled to locations from New York to Los Angeles to San Francisco to Shanghai to Taipei. They’ve been used almost every week of their lives, for speaker measurements, live music recording, cable TV shows, trade shows and in my own audio systems. Yet in all that time neither of them has ever failed or ever needed repair.

I’m talking about a pair of microphone cables I built for live recording. Inspired by an AES presentation about stereo miking techniques, and by Marantz’s offer to loan me a then-exotic and expensive CD recorder, I borrowed a DAT machine and some microphones with interchangeable capsules from my friend and mentor Lance Braithwaite, who I was working with at Video magazine. I then dusted off my Chapman Stick, called in my friend George French to play drums, and recorded a few jazz standards in Video‘s test lab using some of the miking techniques I’d heard described at the AES presentation.

I’m talking about a pair of microphone cables I built for live recording. Inspired by an AES presentation about stereo miking techniques, and by Marantz’s offer to loan me a then-exotic and expensive CD recorder, I borrowed a DAT machine and some microphones with interchangeable capsules from my friend and mentor Lance Braithwaite, who I was working with at Video magazine. I then dusted off my Chapman Stick, called in my friend George French to play drums, and recorded a few jazz standards in Video‘s test lab using some of the miking techniques I’d heard described at the AES presentation.

Lance didn’t have any mic cables long enough to get the job done, so I wandered down to one of the pro music stores on 48th Street in Manhattan to pick up a couple. Disappointed by the so-so quality of what the store had to offer, and having recently read that Skywalker Sound used Canare Star Quad cable, I asked for two 20-foot lengths of Star Quad (one red, one blue) and some Neutrik XLR connectors to terminate them with. Having worked a few electronics assembly jobs, my soldering skills are solid, so whipping up a couple of mic cables was easy.

They worked perfectly then, and they still work perfectly today. Here’s a PDF that shows some of the reasons why these cables have lasted so long.

We talk a lot about the sound quality of cables (or if you prefer, the lack of any identifiable sound quality in cables), but I never seem to see any discussion of how durable they are. Sure, many, perhaps most, audiophiles don’t have to change cables all that often, so to them, durability doesn’t matter much. But I do know several audiophiles who change out gear pretty often — either to try new stuff or to enjoy, say, an old favorite amplifier they haven’t used in a while.

If you’re changing gear a lot, it’s critical to have durable cables — cables that can tolerate being stepped on or kinked, connectors built to be disconnected and reconnected thousands of times without breaking, and strain relief that keeps the wires from being broken and the solder joints from pulling loose when you accidentally trip over the cable or pull out a piece of gear while the cable’s still connected. With most consumer-grade and even many professional-grade cables, these concerns seem to come in roughly fourth, after electrical performance, price and cosmetics. Most of the cables I’ve owned have lasted reasonably well, but I’ve experienced quite a few cable failures over the years — particularly with audio interconnects and all types of video cables.

That’s why you’ll still find a lot of Canare Star Quad in my listening room. Say what you want about sound quality, but any cable that works sounds better than any cable that doesn’t.

(By the way, if you’re mordibly curious about the results of the recording sessions George and I did, I still have one MP3 of us playing Thelonious Monk’s classic “‘Round Midnight.” If memory serves, I used dual cardioid mics placed at a 90-degree angle, which is what George and I both thought sounded best, at least in the sub-optimal acoustical environment of a Manhattan office with a linoleum floor and a drop ceiling.)