It’s the time of year for saving money!

Digital? Analog? There’s no difference!

By Roger Skoff

When you stop to think about it, you’ll understand that our

ears are merely devices that respond to changes in air pressure with changes in

the position of their diaphragm (the eardrum) to create varying nerve impulses

that our brain interprets as sound. Microphones do exactly the same thing:

Regardless of what kind or pattern they might be, they all have diaphragms that

change position in response to changes in air pressure to create signal output

– and speakers do the same thing, too, just in reverse: They create changes in air pressure by

changing the position of their diaphragm (usually a cone, dome, or ribbon) in

response to a signal.

Considered from any of those standpoints, the sound we hear – whether

the sweetest music or the sound of gunfire – is really just a succession of

eardrum positions that our brain recognizes, strings together, and allows us to

gather information from. As long as the positions are all there, and are all

correct and in the right order, we can recognize them and respond accordingly.

Recording sound,

whether digitally or by any of the various analog means (LP, tape, optical,

etc.) is therefore, in the final analysis, nothing more than recording a

succession of pressure waves as reflected in the resultant position of the

diaphragm(s) of one or more microphones.

“Ah,” you say, “but what if there is more than one sound? A symphony

orchestra might have more than a hundred players. Or what if the recording

engineer were to use a dozen microphones?”

None of it matters. Ultimately, all of the pressure waves will

sum algebraically at the microphone or all of the microphones will sum

algebraically in the mixer to make only one effective diaphragm position (per

channel or per ear,) at any given instant, and that’s finally where we start to

find some difference between digital and analog recording.

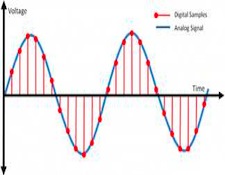

All any kind of recording can do is to record amplitude, as reflected by the net

positive or negative position of the source (the mixer or the single

microphone) diaphragm at a particular instant. With analog recordings, the

number of instants recorded is infinite, comprising, as it does, a continuous

sweep of positional amplitude “readings”.

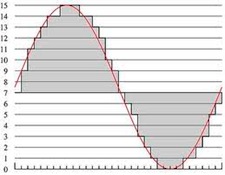

With digital, the number of “readings” is finite, and very much less,

controlled both the number of bits available and the scan rate, which was only

44,100 times a second on the original 16 bit CDs.

44,100 sounds like a big

number, and so does 65,535, the highest number that can be written in 16 bits,

but neither of them is anything at all when compared to the many

umpteen-umpteen-millions that is infinity. And that’s why digital recording

–even digital recording at multiples of 16 bits or 44.1k — can be less than

100% satisfying to many listeners. With only a few possible positions (the bit

count) being written only a few times a second (the scan rate) a low level

(quiet) sound recorded digitally uses only a very few bits, scanned only a

relatively few times per second. All of the positions between the positions possible to write with digital whole numbers

have to be approximated, and all of the positions between the positions scanned

are simply missing.

This results both in missing information and in a phenomenon

called “stair-step distortion”, which can easily be illustrated: The difference

between 64,793 (a high bit-count, high amplitude number) and 64,794 is just a

tiny fraction of one percent, and it’s not only unlikely to be audible, but

almost certain to be “masked” by the other sounds surrounding it. The

difference between the numbers 4 and 5, however, both of which are very low

bit-count, very low amplitude numbers, is COLOSSAL by comparison – a full 25%

(going from lesser to greater), and it’s in the very worst possible place from

a High End audio standpoint.

For High End audiophiles, tiny details like the fifth bounce

off the walls of the concert hall or the silence between notes in a quiet

piece, are of massive importance, and their correct presence or absence can

make all the difference in the world to the believability of a recorded

performance. These tiny details are

where digital can fail and analog, with its infinite resolution and infinite

scan rate is king.

The big numbers, on the other hand, are where digital really

shines. Analog recordings -whether because of tape saturation or the

electromechanical limitations of LP cutting and playback devices – become,

after a point, increasingly distorted as they get louder: exactly the opposite

of digital, which gets more distorted as its numbers get smaller and it gets

quieter.

Either way, all that is ever there is diaphragm position, more

or less well-captured, and it’s always more distorted at one end of the

loudness scale and less at the other.

Which is better? I think the reality is that they’re both just

different sides of the same coin and it’s up to you to decide which side you

like best.

About Roger Skoff

Roger Skoff is the founder of XLO Cables. The company was sold in 2002. Roger is not currently affiliated with any audiophile companies directly but is still passionate about the hobby of audiophilia.