It’s the time of year for saving money!

Last time, in this continuing series about speakers, enclosures, and bass, I started to write about horn speakers and why they were so important to early audio. The reason, of course — at least for purposes of that article – was that horns are LOUD and the electronics in the early days of electric audio weren’t: Amplifiers back then, had nothing like the power they are capable of today, which is clearly shown by the fact that, even in the 1950s – a full two and a half decades after the first “talking picture” (The Jazz Singer, 1927), the McIntosh MC60 (at 60 Watts) was the biggest thing available, and everyone thought it was huge!

During the 1920s, when electrical audio first came along, amplifier outputs usually ran to just a few Watts. That’s why, for the movies, for political and sporting events, and for every other application where lots of people needed to be able to hear the same thing at the same time, speaker designers took a clue from the earliest phonographs (which had used a horn to acoustically “amplify” the signal from the playback “needle”) and by doing so, picked-up an extra 10db of “free” gain ― the equivalent of having an amplifier a full ten times more powerful.

During the 1920s, when electrical audio first came along, amplifier outputs usually ran to just a few Watts. That’s why, for the movies, for political and sporting events, and for every other application where lots of people needed to be able to hear the same thing at the same time, speaker designers took a clue from the earliest phonographs (which had used a horn to acoustically “amplify” the signal from the playback “needle”) and by doing so, picked-up an extra 10db of “free” gain ― the equivalent of having an amplifier a full ten times more powerful.

In those early days, the big issues were speech loudness and clarity, and – possibly because it couldn’t be effectively recorded back then — there was little concern for such musical niceties as bass or high treble.. Many of us have heard the sound of the recordings of the ’20s and ’30s, and it was pretty awful – even when played on the best modern equipment and speakers. By the 1940s and ’50s, however, recording practice and technology was (although still in mono, except for laboratory work and rare exceptions like Disney’s Fantasia [1940]) vastly improved; men like H.H. Scott and Avery Fisher were working to create the new phenomenon of “high Fidelity” sound; and, all of a sudden, bass was there and waiting to be played back.

Amplifiers were still generally low-powered, though, (The McIntosh MC30 – at 30 Watts – was both more affordable and more popular than the behemoth MC60, and my first integrated amplifier [we just called them “amplifiers” in those days] was the 20 Watt Eico HF-20), so the incentive was still there for horn speakers to make things louder. The problem was that, while horns are just fine, and are still used, even today for midrange and tweeter applications, the size a bass horn must be is directly related to the lowest frequency it has to reproduce, and a horn for even moderately deep bass must be HUGE!

Amplifiers were still generally low-powered, though, (The McIntosh MC30 – at 30 Watts – was both more affordable and more popular than the behemoth MC60, and my first integrated amplifier [we just called them “amplifiers” in those days] was the 20 Watt Eico HF-20), so the incentive was still there for horn speakers to make things louder. The problem was that, while horns are just fine, and are still used, even today for midrange and tweeter applications, the size a bass horn must be is directly related to the lowest frequency it has to reproduce, and a horn for even moderately deep bass must be HUGE!

Last time (in Part 8 of this series), I mentioned Martin Colloms, who, in his book High Performance Loudspeakers (Halsted Press, 1978) had given formulae for, among other things, calculating the length, taper, and final opening (“mouth”) size for horns of various styles for use at all audio frequencies. To illustrate just how big a horn needs to be for even moderately deep bass frequencies, I told you that, according to him, (on page 88) even to get down to just 40 Hz (no big deal at all by modern standards) a horn would need a mouth size of “5.9 m2“, which even Colloms said “… would need to be custom built into a location as part of a fixed structure, and is clearly impractical for most domestic situations.”

Just exactly how impractical it is becomes obvious with just a little arithmetic: The square root of 5.9 meters2 (what Colloms described as the minimum mouth size to pass 40 Hz) = 2,43 meters, 2,43 meters x 39,37 inches per meter = 95.63 inches (as either the height or the width of the required horn mouth) 95,63inches ÷ 12 inches per foot = 7.97 feet, just 0.37 inches (a little less than 1 centimeter) short of 8 feet (=96inches), which is the legally established standard floor-to-ceiling-height of every built-to-code home listening room in the United States.

Just exactly how impractical it is becomes obvious with just a little arithmetic: The square root of 5.9 meters2 (what Colloms described as the minimum mouth size to pass 40 Hz) = 2,43 meters, 2,43 meters x 39,37 inches per meter = 95.63 inches (as either the height or the width of the required horn mouth) 95,63inches ÷ 12 inches per foot = 7.97 feet, just 0.37 inches (a little less than 1 centimeter) short of 8 feet (=96inches), which is the legally established standard floor-to-ceiling-height of every built-to-code home listening room in the United States.

That means that, if you want a 40Hz horn in your standard-height listening room, the horn mouth will take up all but 0.37″ of your available room height (leaving just enough, maybe, to put a thin carpet under it) and, if positioned so that it faces forward from the back wall, the horn mouth will also take up just under 8 feet of the room’s width, NOT including all of the “taper length” of the horn from throat-size to mouth size, which could, even if the horn is “folded” to make it more compact, be considerable and leave it extending far into your room. Finally, if you want your bass in stereo (not absolutely necessary; some people do use just a single subwoofer in their systems), you’re going to need two horns. At 8 feet wide, each, plus whatever distance you allow between them for stereo imaging, that’s going to make for either a very large listening room or a very large problem.

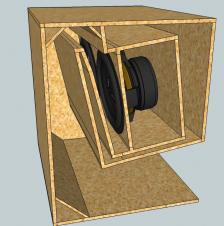

It was Paul Klipsch who, in 1940, found and patented the solution: If your horn is going to be as big as your room, why not just use the room, itself, as your horn? That’s what Klipsch did, placing the speaker enclosure into the corner of the listening room, and using the walls forming the corner as elements of the horn and the speaker enclosure, itself (and all of the folded “taper elements” that it contained) as a sort of “phase plug” to ensure correct propagation of the sound. Klipsch founded his company in 1946 and the first “Klipschorns” were sold in 1947, to be followed not long thereafter by – among other corner horn designs – the Electro-Voice Patrician and the James. B. Lansing (now “JBL”) Hartsfield.

It was Paul Klipsch who, in 1940, found and patented the solution: If your horn is going to be as big as your room, why not just use the room, itself, as your horn? That’s what Klipsch did, placing the speaker enclosure into the corner of the listening room, and using the walls forming the corner as elements of the horn and the speaker enclosure, itself (and all of the folded “taper elements” that it contained) as a sort of “phase plug” to ensure correct propagation of the sound. Klipsch founded his company in 1946 and the first “Klipschorns” were sold in 1947, to be followed not long thereafter by – among other corner horn designs – the Electro-Voice Patrician and the James. B. Lansing (now “JBL”) Hartsfield.

The way the corner horn worked to get proper driver-to-air coupling in a much reduced space was simple: Let’s take a look at it using Martin Colloms’ 40Hz horn mouth specification and the Pythagorean Theorem: If you have a 90° corner (call it “AB”) and you use the side walls extending away from it (call them “A” and “B”) as part of the flaring length of your horn, the development of the horn to 40 Hz capability will use – but not block to other use (remember that this is an acoustical and not physical horn that we’re creating and that the “horn segments” are already there — 5.667 feet (5′ 8″) of each of those two walls. And the horn’s mouth (Call it the hypotenuse, or “wall C”) will extend 4 feet into your room – even if the speaker enclosure, itself, doesn’t. (If A and B are equal and “C” [the hypotenuse], is 8 feet wide then, as per Pythagoras, A2 + B2 = C2,, which means that if C= 8feet , then C2 will equal 64 feet and each of the two equal-length side walls will be the square root of half that amount long [feet = 5 feet 8 inches] and the center distance from C to the corner [“AB”] will be 4 feet, exactly [= ½ of the hypotenuse]).

This use of existing elements (part of the floor, too) was brilliant, and allowed Klipsch and later designers to get low (ish) bass in real-sized rooms.

There’s more, obviously, but I’m out of space for now.

See you next time!