It’s the time of year for saving money!

I’ve talked with any number of Audiophiles, Music Lovers, and outright Hi-Fi Crazies (like me and my pals) over the years, and asked them what it is that “turns them on” about their system. As you can imagine, the answers have been all over the place — from imaging and soundstaging (like me), to clarity, (for a lot) to harmonic richness, to freedom from distortion, to transient attack and decay (like Tony DiChiro) to just plain “believability” (like Tom Miiller), to practically anything else at all that you can imagine. But of everything possible, the almost universal sine qua non has been good bass.

It used to be that if you wanted good bass, the speakers you bought (or speaker, back in the days of mono) had to be big, and if you wanted to get good bass from a horn-type speaker, it had to be HUGE! One famous early-days audiophile cartoon (I’m going to guess that it may have been in High Fidelity Magazine) carried it so far as to show a house whose entire roof was a single downward-pointing bass horn, and although I doubt that such a thing was ever actually done, I know for a fact that many an audiophile installation did something at least similar.

It used to be that if you wanted good bass, the speakers you bought (or speaker, back in the days of mono) had to be big, and if you wanted to get good bass from a horn-type speaker, it had to be HUGE! One famous early-days audiophile cartoon (I’m going to guess that it may have been in High Fidelity Magazine) carried it so far as to show a house whose entire roof was a single downward-pointing bass horn, and although I doubt that such a thing was ever actually done, I know for a fact that many an audiophile installation did something at least similar.

The way a speaker produces sound is really simple: a diaphragm of some sort (usually a cone or a dome, although panels and other types have certainly been used) moves back and forth and creates, in front of it (in the direction of its motion) a zone of high pressure air and, behind it (following the moving diaphragm), a zone of low pressure air. Those pressure zones (waves) are the sound. When the diaphragm stops moving forward and starts in the opposite direction, the same thing happens, only in reverse, with a high pressure zone forming behind the diaphragm and a low pressure zone forming in front of it. The problem with bass, or any frequency where the wavelength is greater than the diameter of the driver producing it is that pressure waves produced by and spreading from the front of the driver can meet the out-of-phase pressure waves produced by and spreading from the back and cancel, leaving little if any audible bass, no matter how much is actually being produced by the driver.

The easiest way of improving a speaker’s audible bass response is simply to keep the front and back waves from ever meeting and canceling, and that can be done as simply as just mounting the driver in a hole in a large board so that the front of the diaphragm is to the front of the board and its back is to the back. That way, if the edges of the board are more than half the wavelength of the lowest desired frequency from the edge of the driver, the board will always be in the way; the front and back waves will never meet and cancel; and you’ll hear whatever bass the driver can make.

That big board is called an “infinite baffle” because as long as it’s big enough to stop the waves from meeting it IS effectively “infinite”. It will also, if we’re looking to hear deep bass, be quite large: Half a wavelength at 20Hz is something like 28 feet (8.57 meters) long, depending on ambient air pressure, humidity, and temperature, so the board, to be effective, would have to be something more than twice that distance (plus the size of the driver) from edge to edge in every direction.

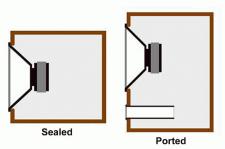

Obviously the vast majority of people could never get a thing that size into their house, so what else can be done to keep the waves from meeting? Well, you can fold the edges of the board together to make a sealed box (still -if it’s big enough – called an “infinite baffle”). A sealed box will certainly keep the waves from coming together and will certainly be much smaller than a board to do the same thing. If you make it TOO small, though, the increase or decrease in pressure of the trapped air inside the box caused by the movement of the diaphragm will resist the diaphragm’s movement in either direction and result in an effective loss in bass performance. The answer? Use a big enough box. The Bozak B-310, which used four 12 inch woofers to make genuine 24Hz bass, even in the early 1950s, when 50Hz was considered adequate performance, had an infinite baffle enclosure of 16 cubic feet–about the same size as the then-average full-size home refrigerator.

Obviously the vast majority of people could never get a thing that size into their house, so what else can be done to keep the waves from meeting? Well, you can fold the edges of the board together to make a sealed box (still -if it’s big enough – called an “infinite baffle”). A sealed box will certainly keep the waves from coming together and will certainly be much smaller than a board to do the same thing. If you make it TOO small, though, the increase or decrease in pressure of the trapped air inside the box caused by the movement of the diaphragm will resist the diaphragm’s movement in either direction and result in an effective loss in bass performance. The answer? Use a big enough box. The Bozak B-310, which used four 12 inch woofers to make genuine 24Hz bass, even in the early 1950s, when 50Hz was considered adequate performance, had an infinite baffle enclosure of 16 cubic feet–about the same size as the then-average full-size home refrigerator.

The closed box approach certainly worked, and one variant of it that Hi-Fi Crazies of the time used was to cut a hole in the wall from their listening room to the room adjoining it and mount the speaker in the hole. That way, depending on how you looked at it, either they got rid of the need for a box or they put themselves into the box with the driver. Either way, it worked… and they also got sound (albeit without all of the highs) in the adjoining room.

Another way of keeping the front and back waves from ever meeting was to simply lose the back wave. That’s what “transmission-line” enclosures (which I’ll write about later) do, and it was also done “DIY” in at least the two examples following: One that, if I remember correctly, was even written-up in Popular Electronics (which also first published an article on the to-become famous “sweet sixteen speaker array”) was to mount the speaker (obviously mono, unless you happened to have two fireplaces in your listening room) to a board and affix the board so that it tightly plugged the front of your fireplace. If done properly, that gave you direct forward radiation and allowed the back wave to vent out harmlessly into the atmosphere through the chimney.

Another way was to use a smallish but rigid sealed box with the driver mounted to its front and a vacuum- cleaner hose (or something similar) to vent to the outside or another room. Both worked quite well to get rid of the back wave, providing that the seal, either from the board to the fireplace or between the box and the hose didn’t leak and allow the waves to meet and cancel.

Another way was to use a smallish but rigid sealed box with the driver mounted to its front and a vacuum- cleaner hose (or something similar) to vent to the outside or another room. Both worked quite well to get rid of the back wave, providing that the seal, either from the board to the fireplace or between the box and the hose didn’t leak and allow the waves to meet and cancel.

Other ways to make better bass involved not losing the back wave, but using it to augment the front wave for louder and deeper bass. I’ll write about some of those, next time.

See you then.