It’s the time of year for saving money!

In part 1 of this new series, I told you that the way almost all speakers make sound is by moving a diaphragm back and forth. (There are certain exceptions to this, of course, like the Ionovac or Plasmatronics speakers, but for various reasons, they were never popular and are no longer around, except as curiosities) As the diaphragm moves forward, I told you, it moves the air ahead of it, creating a moving high pressure zone in front of the diaphragm and a moving low pressure zone following it. Then, when the diaphragm changes direction to move back to its original position and on to its next “turnaround” point, the pressure zones reverse, always keeping the high pressure zone ahead of the diaphragm in the direction of motion and the low pressure zone following. Those moving pressure zones are the sound “waves” that we hear, and, the fact that the waves from the front and the rear of the diaphragm are necessarily out of phase with each other poses, at least at bass frequencies, both problems and opportunities for the speaker designer.

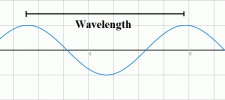

I told you, last time, about the problem of cancellation when the front and back waves coming off the speaker meet: This will always happen in a free air environment if the diameter of the driver is less than half the wavelength of the frequency it’s producing, and no matter how much bass your speaker may actually make, you won’t be able to hear it if it’s being canceled-out.

I told you, last time, about the problem of cancellation when the front and back waves coming off the speaker meet: This will always happen in a free air environment if the diameter of the driver is less than half the wavelength of the frequency it’s producing, and no matter how much bass your speaker may actually make, you won’t be able to hear it if it’s being canceled-out.

One way to eliminate this cancellation is to simply mount the driver to a board big enough that it will keep the front and back waves from the driver from ever meeting. And how big does that have to be? Well, the wavelength of any frequency is equal to the speed of sound (in air, normally considered to be 1125 feet [343 meters] per second) divided by the number of cycles (Hertz) per second. 1125 feet (343 meters) divided by, for example, 20 gives a wavelength of about 56 feet (17 meters) for a 20 Hz deep bass tone. And to block cancellation of that you need a board with a distance of something more than half the wavelength of the lowest desired frequency (in this case, 20 Hz) away from the driver, so that – if we really want to be able to make 20Hz bass – we will need a board at least 56 feet (one full wavelength) plus the diameter of the driver and a little more — from edge to edge in every direction.

Obviously that’s far too big for people to fit into any ordinary house, so alternative approaches have had to be found over the years to keep the front and back waves from canceling. One that I mentioned last time was simply to “bend” the board into a closed box to keep the waves apart. That can certainly work, as long as the resulting box is not too small (which can create other problems), and so can such other things as mounting the driver in a hole in a wall so that the front wave from it goes into one room and the back wave goes into another.

All kinds of things have been tried, successfully and otherwise, for dealing with the back wave cancellation problem by simply getting rid of it and listening to the front wave, only. I mentioned a couple of those last time, including the “transmission line” enclosure, which I’ll write more about later, and actually venting the back pressure from the diaphragm into another space or dumping it into the atmosphere outside the listening room.

I also said that there are ways of using that rear, out of phase pressure to augment and actually improve your speakers’ bass response. Some of those are what this second part of this series will describe.

I also said that there are ways of using that rear, out of phase pressure to augment and actually improve your speakers’ bass response. Some of those are what this second part of this series will describe.

If you stop to think about it, you’ll find that using the back wave.is really a good idea: Whatever sound the front of the diaphragm produces, the sound from the back of the diaphragm ― because it’s produced by exactly the same excursion of the same diaphragm, produced by exactly the same amount of input power ― will be identical. So if you could find a way to add the sound levels from both sides of the diaphragm together without them canceling, it would be twice as loud (3dB louder) or – whichever you choose – require exactly half as much amplifier power.to produce the same level of volume.

To my knowledge, the first technique to actually do this was the bass reflex speaker enclosure. Instead of actually somehow tricking the two out-of-phase pressure waves into coming together without canceling, though, this uses the principle of the Helmholtz Resonator to excite the air inside a ported box to produce a new bass signal to reinforce the signal from the front of the driver.

Everything in the universe has a fundamental resonance frequency – a frequency at which it will resonate when stimulated, regardless of the frequency of the stimulus. That includes the air inside a semi-closed box (an organ pipe or a speaker enclosure, for example). What a properly designed bass-reflex enclosure will be designed to do is to resonate at a frequency lower than the fundamental resonance of the driver. This can effectively reverse the phase of the pressure waves coming out of a hole (a “port”) cut in the box and cause the pressure waves escaping from it to be in phase with, and to augment the pressure waves coming off the front of the driver.

This system does work, but it does have certain problems: For one thing, the in-phase pressure coming out of the box will always be one cycle (360° of phase) behind the driver’s front wave, which can “soften” or “Smear” bass transients. For another, because the box can have only a single fundamental resonance frequency, there is often a tendency toward “one-note” bass.

This system does work, but it does have certain problems: For one thing, the in-phase pressure coming out of the box will always be one cycle (360° of phase) behind the driver’s front wave, which can “soften” or “Smear” bass transients. For another, because the box can have only a single fundamental resonance frequency, there is often a tendency toward “one-note” bass.

Many things can be done to mitigate these problems and, in fact, a great many bass-reflex speakers, including the big, violently expensive and exquisitely good, Goldmunds and my own very impressive ACA Seraphims will provide wondrously deep, “tight”, and – when called for – head-crushing and room destroying bass.

I’ll tell you some of the ways it’s done next time.

See you then.